ArtSeen

Sean Scully: The Shape of Ideas

On View

Philadelphia Museum of ArtApril 11 – July 31, 2022

Philadelphia

More and less, neither more nor less. Perhaps an entirely other question.1

—Jacques Derrida

Nothing could shed light more eloquently on Sean Scully’s oeuvre of the past five decades than the subtitle of the riveting retrospective that is currently on view at the Philadelphia Museum of Art: The Shape of Ideas. Mirroring a primary definition of art as a form of representation and echoing the Platonic and Aristotelian debate on form and content, the rhetoric of the title takes on a Beckettian quality in light of the primarily abstract pictorial language of Scully’s work. Here the boundaries of form and content dissipate, as medium and message are rendered interchangeable, undermining the closure of meaning and anticipating those interpretations that emerge from the perception and intuition of the observing subject.

Expertly curated by Timothy Rub and Amanda Sroka, this impressively presented exhibition methodically unravels Scully’s lifelong formulation of a set of geometric motifs, often organized within gridded configurations as blocks of color. Over one hundred works by Scully, spanning from 1972 to 2021, are on view in the Dorrance Special Exhibition Galleries and Korman Galleries. They encompass paintings, watercolors, drawings, aquatints, woodcuts, etchings, color lithographs, and a digitally-printed suite. Presented chronologically to a great extent, Scully’s work also unfolds thematically, a progression marked by the section titles “Variations on the Grid,” “A Stripe Like No One Else’s,” “Multipanel Paintings,” “Insets and Checkerboards,” “Wall of Light,” “Doric,” “Landlines and Windows” and “Sean Scully as Printmaker.” In the preface of the superb catalogue of the exhibition, Marla Price aptly notes, “The systematic elements of [Scully’s] early works have never really disappeared as he continues to explore different combinations of building units or motifs and then pair them with emotion and content.”2

“A friend of mine asked me if paintings spoke. If it was possible,” recounts Scully. “I said yes: but with the language of light.”3 As vertical and horizontal delineations in Scully’s visual fields celebrate abstraction’s autoreferentiality by inviting the viewer to reflect upon the optical and haptic properties of a given work, geometric segments of color impart rhythmic interchanges of shading and luminosity. Scully’s “language of light” operates through brush-marked surfaces with multiple strata of tonal variations, where primary geometric forms and topographies explore the experience of sameness and difference, the relation of the image to the framing edge, closure and openness of forms, optical movement and stasis, limitation and extension of shapes, and the function of parts in relation to the whole.

A “pioneer of a new kind of abstract painting” has been Deborah Solomon’s succinct verdict of Scully, deeming his achievement as a bridge between the utopian model of modernism and the works of such contemporary practitioners of abstraction as Amy Sillman, Mark Grotjahn, and Mark Bradford.4 Donald Kuspit has described Scully’s “Wall of Light” series as having “a self-enclosed Romanesque rather than an open Gothic look,” characterizing them as evocations of walls, rather than windows, through which light appears to stream.5 The late philosopher and art critic Arthur Danto has described the artist’s own poetic intent by claiming, “Scully is far from a formalist artist, and expects his work to transmit metaphors of the widest human relevance.”6

Scully’s output, since its outset, has been a relentless conjugation of the formalist properties of abstract painting, proposing the work as a physical manifestation of an “idea” in and of itself, a self-contained visual realm that nonetheless remains in conversation with the contemporary status and history of abstract painting. The Shape of Ideas demonstrates Scully’s desire to investigate and reinvent geometric abstraction with an expressive virtuosity that pays homage to the formalist logic of modernism, simultaneously expanding its aesthetic and hermeneutic possibilities.

Frame and surface: these two structural elements recirculate steadily throughout Scully’s practice, hazing the distinctions between object and image, where line and color disintegrate the taxonomy of figure and ground. This enterprise reveals itself through reiterations of pictorial frames within optical spaces (as in Green Light [1972–73]), through the assembly of multiple panels of varying measurements (as in Backs and Fronts [1981]), through a dialectic between gesture and frame (as in Heart of Darkness [1982]), through protruding and sunken surfaces (as in The Fall [1983]), through insets and gestural veils of paint (as in A Bedroom in Venice [1988]), through interchanges between tactile and pictorial lines (as in Vita Duplex [1993]), through a reinvention of the classical modernist grid (as in Mooseurach [2002]), through a geometry of dramatic painterly gestures (as in Landline North Blue [2014]).

The titles of these paintings may perform as subtexts, threatening to breach the bounds of abstraction’s autonomy. Similarly, the writings and interviews of Scully reveal his conviction in abstract painting as a conduit for narrative, emotion, poetry, idea and thought. Nevertheless, as Scully has offhandedly stated, “I’m not trying to make paintings that are decipherable and ‘understood,’ because I don’t think that’s what is needed; that becomes a dead thing. I try to make paintings that are not conquerable, that can be reused over and over again, that are not merely designs. … My paintings are about flaws and about life (street life).”7 In 1989, reading his paintings as “fierce, concrete and obsessive, with a grandeur shaded by awkwardness,” art critic Robert Hughes would assess Scully’s recurring leitmotif as “a stripe like no one else’s.” Indeed, Scully’s self-interrogative dialectic runs throughout this survey: throughout, the spectator confronts a formalist language probing itself from within.

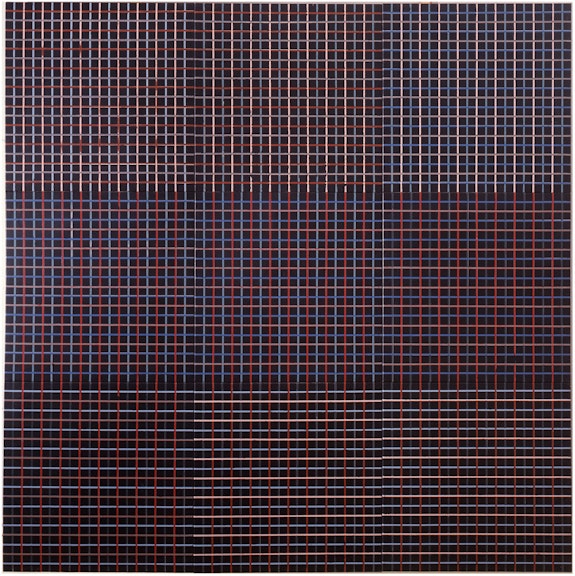

Upon entering the section titled “Variations of the Grid,” the first painting the visitor confronts reveals itself as a latticed abyss, an optical quandary, an unmistakable embodiment of Plato’s Allegory of the Cave that addresses reality as opposed to perception. Inset #2 (1973) is an eight-foot square acrylic painting Scully executed in response to the geometric patterns of Hard-Edge painting and Op Art, only to pair the objectivity of geometry with the amorphousness of Abstract Expressionism and Color Field painting. Frank Stella, Ellsworth Kelly, Bridget Riley, Mark Rothko and Helen Frankenthaler are a few of the paradigmatic names that Inset #2 evokes, except here Scully addresses the discrepancies of reality and appearance by inventively integrating the formalist contraries of linearity and painterliness, flatness and shading, surface and depth.

In hindsight, Inset #2 now registers as a formative example of Scully’s distinctive pictorial language, espousing a geometry that is more carnal than cerebral, more visceral than rational, more elusive than Stella’s famous “what you see is what you see.” That carnal geometry can now be read as a revelation of subjectivity, despite the distinctly objectivist associations of its ordered series of horizontal and vertical lines. In Scully’s hands, abscissas and ordinates become approximations that structure pictorial space as a dialogue between the rational and irrational, the ideal and real, essence and appearance, the logical and lyrical. “This is my way of making the paintings human,” Scully has stated, claiming that a painting “represents the flesh of the body.”8

In 1972, through Harvard Frame Painting, Scully proposed a definition of painting as a screen, a physically open entity, an amplified disclosure of the warp and weft threads that structure the weave of the linen support. Exhibiting structural interchanges among wooden frame, felt, sacking and paint, the armature of this work registers as a visual interrogation of painting’s basic structure. As a gridded matrix encapsulating the literal opacity and transparency of real objects and real space, Harvard Frame Painting exists between painting and sculpture, evoking the disorderly knotted ropes of Eva Hesse just as readily as the comparatively methodical idiom of Mondrian. We are here reminded of Hesse’s astonishing Metronomic Irregularity I (1966), for instance, a seemingly nonrepresentational triptych where the mediums of painting and sculpture coexist, provoking extra-pictorial possibilities of reading, where the Apollonian and Dionysian converge.

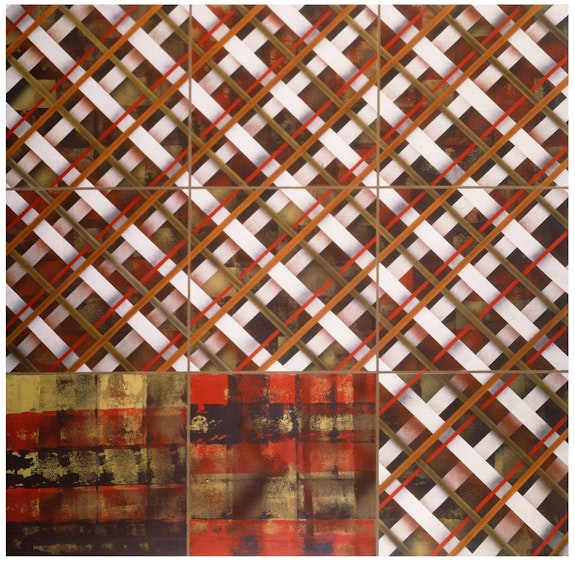

Black Composite (1974) is a diagrammatic acrylic painting comprising nine square canvases assembled as a matrix, where each panel features a linear grid in various colors, all set against black backgrounds. As the horizontal and vertical lines here have been fashioned with the aid of tape during successive phases of realization, Black Composite reveals accidental marks left from the partly mechanical process of defining the complimentary and contrasting lines. To thus “use the means of order to create disorder … and to make something that you couldn’t really break down analytically” has been Scully’s aim, the desire that motivated him to adhere to the conventional medium of paint, despite the medium’s abandonment by many of his classmates at Newcastle University in England in wake of the 1968 political and social protests across the globe.9

Scully’s move to New York in 1975 would inaugurate a half-decade of so-called Minimalist paintings and works on paper, as exemplified by the acrylic painting Grey Red (1975) and oil painting Fort #3 (1980). The shift from the medium of acrylic to oil allowed the layering of a range of colors, altering the observer’s chromatic grasp of the surface when it is examined up close. Though Fort #3 may suggest an austerity in tune with Minimalism’s employment of the impersonal and fabricated, it simultaneously disrupts this ethic of depersonalization. Scully’s relation to the Minimalist path was at once open and reserved, since the mechanized means of art production favored by that movement would ultimately contravene his commitment to the medium of paint applied solely by hand and his reconciliation of the polarities of geometry and gesture, objectivism, and lyricism. In his incisively written 1979 essay, the late art historian Sam Hunter characterizes these paintings as being “unique today in their particular combination of painstaking method and emotional intensity.”10

The title of Boris and Gleb (1980) signals a shift toward abstraction’s metaphoric potential—here a horizontally striped panel abutting its vertically striped counterpart becomes suffused with Christian iconology. Such a pairing of horizontality and verticality also conjures up the fundamental aspects of man’s vertical position as addressed by Sigmund Freud in Civilization and Its Discontents. The upright posture of the human body, set apart from the horizontality of animals, as Freud argues, would lead to civilization’s fateful condition: “Men have gained control over the forces of nature to such an extent that with their help they would have no difficulty of exterminating one another to the last man.”11 As Scully has firmly indicated, oil paint has an indescribable capacity to “resist the deadening ambition of the modern world to control everything, absolutely.”12

At this point, Scully abandoned the use of tape so as to allow the brushstroke to come to visibility, leading to outstanding multi-panel paintings such as Rose Rose (1980), Precious and Blue (both 1981), and the acclaimed Backs and Fronts (1981), first exhibited in Critical Perspectives: Curators and Artists at PS1 in New York in 1982. Though it was initially titled Four Musicians and accordingly comprised four vertical panels, eight additional panels would be added, culminating in a monumental work through which “Scully turned his Minimalism inside out into a species of Expressionism,” according to David Carrier.13 As Rub notes in the exhibition catalogue, Backs and Fronts represents the most decisive step in Scully’s career.14

Named after islands, Elder, Ridge, and Bonin (all 1982) are intimately scaled works that were executed during Scully’s residency at the Edward F. Albee Foundation in Montauk, New York. By overlaying one striped panel upon another, Elder engages with real space, incorporating real shadow into what has now become an abstract relief. These works would soon be translated into mural-scale paintings that occupied Scully’s practice for half a decade, as evidenced by The Fall (1983), Tonio (1984) and Falling Wrong (1985).

The singular place these abstract reliefs occupy within the history of the second half of the twentieth century prompts dialogues with the work of Louise Nevelson, Ellsworth Kelly, Frank Stella, Lee Bontecou, and Donald Judd, to name just a few. From today’s perspective, the absorbing play of light and shadow upon works by such contemporary practitioners as Imi Knoebel, Leonardo Drew, Rachel Lee Hovnanian and Gabriel J. Schuldiner suggests aesthetic exchanges with Scully’s visual syntax of the 1980s. The decision to treat his painting as a sum of protruding and receding objects rather than a mere image certainly informs Scully’s subsequent move: his invention of the inset, a signature device that he continues to explore in his current practice.

In pairing arrangements of geometric forms and chromatic luminance that define both real and pictorial surfaces, Scully’s work simultaneously triggers and unsettles the semantic values of abstraction and illusion, representation and non-representation, figuration and non-figuration. If “both abstract and representational” or “neither abstract nor representational” might easily describe the viewer’s experience or interpretive task, such phrases seem also to be welcomed by Scully, who has insistently declared, “I’m not trying to say anything different from what you want to say; I want to say the same thing. I want to make visible what we feel—not just what I feel, but what we feel.”15 As Scully aims to represent through painting what language cannot, his project brings to mind Vasily Kandinsky’s attempt to do the same. Drawing on Jacques Derrida and Edmund Husserl in discussing Kandinsky’s ambition, Leah Dickerman writes, “Derrida … notes Husserl’s blind spot, his failure to recognize that all perception is itself framed by speech and cannot exist outside it.”16 But for Scully, it is precisely the extent to which painting can counter the compartmentalized structure of language, and the extent to which perception can exist outside of speech, that is most crucial. Here, seams of luminosity overturn flatness, exposing the epistemological sutures of language and thought.

-

Jacques Derrida, Margins of Philosophy (1972), trans. Alan Bass (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982), p. 173.

-

Marla Price, “Preface”, in Sean Scully: The Shape of Ideas, eds. Timothy Rub with Amanda Sroka (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2020), p. 9.

-

Sean Scully, “The Language of Light” (2000), in Inner: The Collected Writings and Selected Interview of Sean Scully, eds. Kelly Grovier and Faye Fleming (Berlin: Hatje Cantz, 2016), p. 85.

-

Deborah Solomon, “The Duane Street Years” (2006), in Sean Scully: The Shape of Ideas, p. 237.

-

Donald Kuspit, “Sacred Sadness” (2007), in Sean Scully: The Shape of Ideas, p. 231.

-

Arthur C. Danto, “Between the Lines: Sean Scully on Paper” (1996), in Sean Scully: The Shape of Ideas, p. 238.

-

Scully, “The Sublime and the Ordinary” (1989), in Inner, p. 20.

-

Scully, p. 23.

-

Scully, quoted in Timothy Rub, “Sean Scully: The Shape of Ideas,” in Sean Scully: The Shape of Ideas, p. 21.

-

Sam Hunter, “Sean Scully’s Absolute Paintings” (1979), in Sean Scully: The Shape of Ideas, p. 219. Originally published in Artforum 18, no. 3 (November 1979), pp. 30-34.

-

Sigmund Freud, Civilization and Its Discontents (1930), trans. James Strachey (New York: W. W. Norton, 1964), p. 92.

-

Scully, “Oil Paint” (1995), in Inner, p. 37.

-

David Carrier, cited in Sean Scully: Catalogue Raisonné of the Paintings: Volume II, 1980—1989, ed. Marla Price (Berlin: Hatje Cantz, 2018), p. 61.

-

Timothy Rub, “Sean Scully: The Shape of Ideas,” in Sean Scully: The Shape of Ideas, p. 41.

-

Scully, “Empathy” (1986), in Inner, p. 15.

-

Leah Dickerman, “Vasily Kandinsky, Without Words,” in Inventing Abstraction 1910-1925: How a Radical Idea Changed Modern Art, ed. Leah Dickerman (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2012), pp. 46-53, above quote from page 53. See also Jacques Derrida, Speech and Phenomena and Other Essays on Husserl’s Theory of Signs, trans. David Allison (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1973).