I first read Carl Sagan’s Contact and Cosmos in high school, when I was working at a bookstore that let us borrow any book we had at least two copies of on the shelves. I loved them then and was excited to revisit these books in the course of my research for The Possibility of Life. A scene from Cosmos had stayed with me—and confounded me—for almost twenty years, and I was ready to make new sense of it. But when I got to the place in the book where the scene should have been, the chapter just ended.

Luckily, I was reading an e-book, so I could search anus… Zero results.

Let me explain.

The scene I remembered is in a classroom—I don’t know if Sagan was teacher or student—and the class is split into groups, each tasked with designing an alien life-form. The professor looks at their anatomy sketches and chides, “Where’s its anus?” What had haunted me across the decades was my confusion: Was the professor closed-minded, or were the students being careless? There was meant to be a lesson there, but unable to parse it I was stuck in that very teenage feeling of knowing the adult world had a meaning I couldn’t access.

But now, researching an entire book on aliens, I was ready to finally figure it out. And it just wasn’t there. It was even harder to google:

“Where’s its anus”

“alien anus”

“anus Sagan”

Nothing. The last one was weirdly thwarted by the fact that Sagan once sued Apple for calling him a butt-head.

I thought I was beat, but I once again opened Google Books and searched “where’s the anus.” And there it was, with one word of the search term changed: Sphere. A book I’d read even before Cosmos, a book that’s sort of about how unknowable alien life could be but is also a fun spooky thriller. Sphere is Michael Crichton at his (according to my seventh-grade memories) absolute best. And that pulpy paperback, not Sagan’s opus, was where this formative anus story was found.

Now that I can see the passage, it’s clear that the professor was meant to be at fault. “But many animals on Earth have no anus. There are all kinds of excretory mechanisms that don’t require a special orifice… Who knows what we’ll find?” That’s obvious enough that I must have understood it even when I was twelve—but it had gotten lost in my memory, tangled up in the strangeness of aliens and incomplete imaginings, things even the grown-ups didn’t understand.

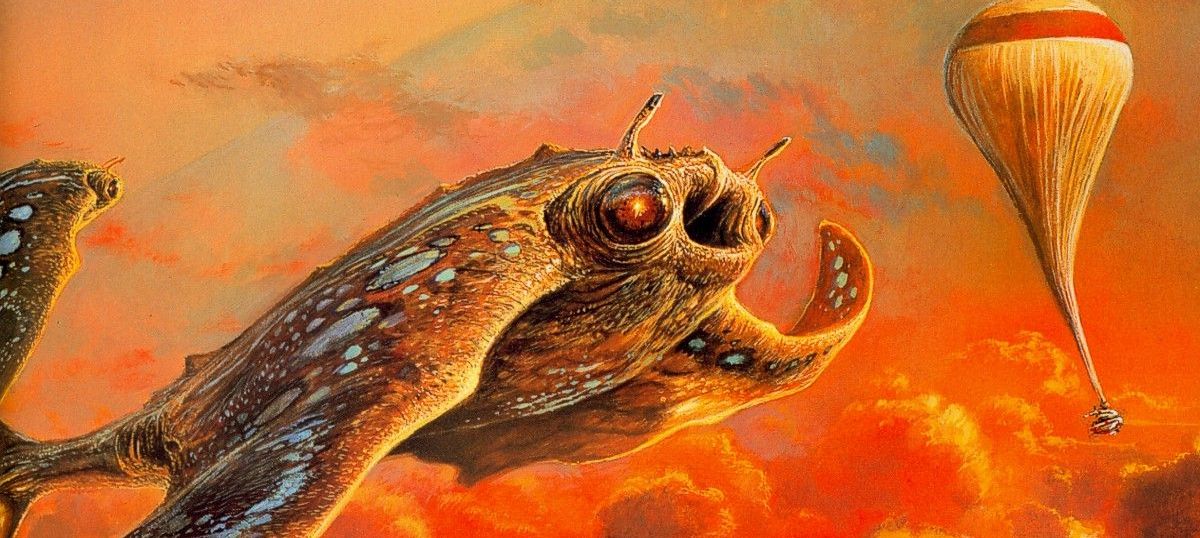

Carl Sagan wanted us to imagine weird aliens, to shatter our anthropocentric habits. If not for scientific reasons, then for spiritual ones.Sagan agreed that alien life was probably incomprehensible. He wrote in Cosmos that even if extraterrestrial life shared our biochemistry, it would have no reason to look at all like life on Earth. But—twist his arm!—he deigned to conjure an example, picking a planetary environment that seemed uninhabitable to more conservative minds, a gas giant like Jupiter. That planet has no solid surface, just a dense atmosphere of hydrogen, helium, methane, and ammonia, where “organic molecules may be falling from the skies like manna from heaven.” Sagan proposed life-forms he called floaters, organic balloons, whale-sized or larger, pumping themselves full of hydrogen or hot gas to rise or sink as needed. “We imagine them arranged in great lazy herds as far as the eye can see.”

Sagan was a fabulist, if not as a scientist, then as a steward of our imaginations. He wanted us to imagine weird aliens, to shatter our anthropocentric habits. If not for scientific reasons, then for spiritual ones. There’s a cosmic humility to be found in understanding that we’re just one of life’s infinitely diverse expressions. Even if we can’t imagine truly strange, truly different life, we push against the inherent xenophobia of our imaginations when we try, while what we know pulls us back like gravity.

You can read almost every alien story as being about this tension—between xenophobia and empathy, between anthropocentrism and the desire to conceive of something else. But there’s also a tension between two functions of science fiction: one, imagining life that’s truly alien; and two, conjuring a kind of alien life that serves a purpose for the humans involved, be it the characters or the readers.

Before we can think about the alien characters humans might meet—the intelligent ones, if not humans, then people—we need to look at the broader ecosystems, the alien organisms imagined or hypothesized to inhabit, in all their diversity, possible alien worlds.

This is where we leave behind the solid footing of scientific research for something more like speculation. We still have science to guide us—extrapolating from what we know about evolution and biology on Earth—but we’re working by analogy and tethered by a pretty thin rope.

Researching multicellular alien life isn’t very practical for scientists. Instead, it’s the possibility of microbial life that rules the lab. When we send probes to other planets, scientists need to have an idea of the possible forms of microbial life and their chemical signatures in order to detect them. Hemmed in by the physics of atomic bonds, researchers can reasonably speculate.

The same parameters also inform how astronomers point their increasingly sensitive telescopes at planets beyond our solar system, also in the hope of detecting life’s chemical traces. But it’s harder to justify lab time and funding for what is ultimately an unexacting exploration of the possible forms of complex life. Scientists work on imagining alien chemistries because we have a plausible need for that knowledge. It just doesn’t make the same sense to spend time thinking about what alien animals might be like.

But that doesn’t have to stop you and me.

*

If you’d never seen a deep-sea anglerfish, would you think it was a friendly fellow Earthling? Or would its grotesque visage, its gaping mouth and the glowing lantern protruding from its forehead, suggest farther-flung origins? What about a platypus, with its patchworked physiology—does a duck-billed, web-footed, egg-laying mammal seem natural to you?

Buried in Earth’s fossil records are extinct animals that match nothing of what we know of animals today, precisely because their lineages dead-ended. If you met an Anomalocaris, a six-foot-long invertebrate cross between a trilobite and a flying carpet with a pair of segmented, spiky trunks, would you think, Ah, yes, the bountiful diversity of my home planet, Mother Earth?

The otherworldly Anomalocaris.

The otherworldly Anomalocaris.

In an office on the fifth floor of the American Museum of Natural History in New York—a warren beyond public access, where the halls are lined with collection cabinets twelve feet high—Mick Ellison has been imagining what extinct animals looked like for the past thirty years. He takes what knowledge science can give him and extrapolates, adding bones to partial fossils and flesh and skin to skeletons. He’s doing his best to bring these creatures back to life.

Buried in Earth’s fossil records are extinct animals that match nothing of what we know of animals today, precisely because their lineages dead-ended.In Ellison’s work, a land-dwelling whale ancestor that lived forty-five million years ago, known only from a single fossilized skull, becomes a hunchbacked creature like an overgrown boar, with a spindly tail, round belly, long snout, and a bristle of hair tracing its spine. Sinornithosaurus, a feathered dinosaur with a chicken-sized body, whose fossils show sharp, delicate bones twisted at unnatural angles, becomes on Ellison’s canvas soft, almost fuzzy, and decidedly birdlike, with a posture that puts its butt high in the air and one long leg slightly raised off the ground. Combined with the animal’s curious gaze, the effect is that of a gentle creature considering whether or not to approach.

Ellison isn’t imagining these animals out of thin air—even when there isn’t a single complete skeleton, let alone impressions left by muscle, feather, or skin. He told me, “It’s all rooted in anatomy and natural science. You see relationships, not only between extinct animals and living animals today, but you can follow lineages. Even if you have a fossil that’s one-of-a-kind, and you don’t have any others like it to compare it to, you can always find things that are closely related to it and then branch out from there.”

The museum’s goals are educational, but they also wrap information in awe. You can read every label in the hall—or you can just look at the T. rex skeleton and go Wow. What you’re absorbing isn’t the facts about a certain extinct animal; facts about what it looked like when it was alive don’t even exist, anyway. Instead, you’re learning a way of engaging with a more connected world across distance and time.

I asked Ellison what he thinks of as his goal when he’s drawing an animal he’s never seen. He said he likes to think of his work as factual and based on evidence, but what guides him isn’t just accuracy. Instead, he said, “My main goal is to try to create something that the viewer can accept as a living, breathing animal.” Especially when it comes to dinosaurs, he said, illustrations often look like dragons or monsters. The problem isn’t that those are wrong, but that they aren’t real.

You don’t need to be a zoologist or farmer to be an expert. We all spend our lives surrounded by animals, in images and in daily life. Cats and dogs, pigeons and songbirds, lions and tigers and bears. But the animals we’re most attuned to are humans. That’s why we’re so sensitive to facial expressions, why CGI people are so difficult to render well, and why, Ellison told me, portraiture is the most challenging form of realistic art. We have an innate sense for what’s human and what’s—sometimes creepily—not. Ellison said we have that for animals, too.

Beyond the question of scientific plausibility—whether the bony protuberances on an animal’s skull are being appropriately used as anchors for powerful jaw muscles—even nonscientists have an intuitive sense of animal realism. Even for an animal we’ve never seen, that no human ever saw. Ellison said, “If you slip up in just one spot, maybe with a certain detail of the anatomy—ears, eyes, posture, or something like that—the illusion just shatters.” The viewer wouldn’t be able to put their finger on what was off, but you’d end up in the uncanny valley of animal realism, with something that looks stuffed or fantastical. Ellison’s job, then, is to be aware of “all the subtle subconscious things that make up something that we believe is natural.”

Alien animals may challenge our intuition for what’s natural like nothing on Earth ever could. It’s an open question whether life on another planet could even be categorized as animal at all. In science fiction, alien life is often at least a little familiar, and you can justify this with science or with narrative needs. We imagine alien animals we’d be able to comprehend, but we hope they might expand our understanding in the process.

The blue-and-green monkey is only on-screen for a moment. It’s not even a monkey—that’s a classification you, the human viewer, make by association. It’s tree-dwelling, and it swings between branches counterbalanced by a long tail. Its face is familiar, with big eyes and a nose and a downturned mouth all where you’d expect to see them. It seems intelligent, too, cocking its head and fixing the camera with an indignant stare before swinging off with the rest of its troupe. But as it does, it grips the branches above itself with two pairs of hands.

Prolemuris gives us an evolutionary link between the hexapod animals and tetrapod people, a scientific logic for what was probably an aesthetic choice.Prolemuris, as they’re known, lives in the forests of Pandora, the setting of the movie Avatar. Theirs is a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it performance, but they’re a crucial piece of James Cameron’s story. Not the story about militant humans and pacifist aliens and the one man who can save them all, but the backdrop so ecologically rich it demands serious consideration, perhaps promotion from backdrop status. Through it, Cameron tells an entirely different story—an evolutionary one.

For the most part, Pandora is inhabited by six-legged animals, hexapods instead of the four-legged ones (tetrapods) we know on Earth. (Most of our six-legged animals are insects.) On Earth, tetrapods dominate in size if not sheer numbers. But on Pandora, six-legged animals run the show: the iridescent direhorse, with a ridge of blue skin where a horse’s mane would be; the viperwolf, a glossy black and vicious predator; the dopey tapirus, a knee-high grazer with globby ridges on its snout. All of these animals—just about all of Pandora’s animals that we see—have six legs. Except for the Na’vi.

The intelligent humanoids of Pandora are strikingly… humanoid. Sure, they’re blue and nine feet tall, but otherwise they look like muscular humans stretched out extra lithe. They have two eyes, a nose, and a mouth just where ours are, which is nothing to take for granted. Most of Avatar’s animals have two pairs of eyes, each set moving independently of the other. They have nostrils on their faces, but also lines of opercula—basically air-gills—on their chests for more robust breathing.

But not so the Na’vi, Pandora’s people. Whether for the sake of viewer empathy or motion-capture ease, the Na’vi have far more qualities in common with humans than any of their planetmates share with other Earthly life.

This is why the two seconds of prolemuris we get matter so much. Like the Na’vi, prolemuris has two eyes, not four, and no opercula. Most importantly, though: their arms. Not two, like the Na’vi. Not six limbs, like other Pandoran creatures. Prolemuris has… two and a half arms? It’s hard to figure out the right math, but basically prolemuris has legs, with two sets of arms that each branch into two hands.

What it looks like, strikingly so, is the partial fusion of a pair of limbs on each side. Prolemuris gives us an evolutionary link between the hexapod animals and tetrapod people, a scientific logic for what was probably an aesthetic choice. Or at least an attempt.

*

Prolemuris’s partially fused limbs are obviously a gesture at evolutionary logic, a way to get from animals with six limbs to people with four. Plenty of Earth animals, like snakes and dolphins, have arms and legs in their ancestry but none today.

But all of those animals lost their limbs because of evolutionary pressure. Snakes’ ancestors lived in burrows and did better with stubbier and stubbier legs until they were gone. A dolphin progenitor thrived in its new aquatic environment as it lost its hind legs, too, while its front limbs worked better as flippers. Just as human embryos sprout tails and then lose them, in a developmental recreation of evolution, dolphin embryos have, for a few moments, hind legs.

But paleontologist, author, and science educator Katie Slivensky points out that a tree-climbing monkey-type is the very last animal who would find four limbs evolutionarily advantageous over six. More hands on unfused arms would make a monkey better at climbing and swinging, faster and more dexterous.

Making matters worse, Slivensky wrote in a post on her blog, “If any animal on Pandora should fuse limbs…I t would be these ground-dwelling ones.” Animals that run tend to evolve toward less contact with the ground—a horse’s hoof, for example, is actually a single toe. “But in every instance of a ground-dwelling critter on Pandora, it of course has six limbs.”

This isn’t about policing pop culture for scientific fidelity, of course. Slivensky reminded me when we spoke, “A lot of pop culture goes more for the imagination than the accuracy.” But, she added, if you’re going to not only invent an alien creature but also depict its evolutionary context, “…it’s actually really easy to just talk to someone for five minutes and get an accurate scientific take on something. It gives you that extra layer of realism.” Even for a lay audience, scientific accuracy is one way to trigger that subconscious click, that sense that this is something real and alive.

Instead, Avatar’s logic seems to me to run on a spectrum from like people to not. The Na’vi are most humanoid, the common animals are less, and the monkey-creatures get halfway. But evolution doesn’t follow that anthropocentric logic. It doesn’t follow most of the logic human minds want to impose on it at all.

________________________

Excerpted from The Possibility of Life by Jaime Green, Copyright © 2023 by Jaime Green. Published by Hanover Square Press.