The architectural language of the most well known member of the Paulista school was intentionally used as a political weapon

The architecture of Paulo Mendes da Rocha speaks of the construction of America, a territory from the postcolonial time, a ‘New World’ found in Brazilian anthropologist Darcy Ribeiro’s O Povo Brasileiro from 1995. His architectural discourse is founded on the construction of a landscape that challenges the centrality of Europe, where ‘subalternity’ is overtaken by a strong sense of self-determination. In fact, Mendes da Rocha is constantly using his work to make the European West recognise its responsibility for the contemporary disaster that haunts the American continent: as he argues, ‘only something great can degenerate’.

Mendes da Rocha points to an idea of modernity that – despite being abandoned in the West around the 1960s onwards – was seen by Brazilian architects as an essential tool to fight the dictatorship that commenced in Brazil in that decade. Their work demands a historic explanation rooted in the battle fought by men like Mendes da Rocha after the 1964 Brazilian military coup. More than ever, these legacies must be acknowledged: since the election of Jair Bolsonaro as president of Brazil – a former member of the military and a revisionist of the harmful effects of the dictatorship – this history assumes a renewed potency and importance.

0301 paulistano armchair paulo mendes da rocha architectural review

The Paulistano chair (1957) was made of a single bended steel bar

Somehow, the modern discourse cyclically restored by modern architects is used as a means of political activism. For Mendes da Rocha, it is a way to ‘resist the disaster’: a vision of the world based on a humanist conviction that returns to the postwar architectural culture, particularly in tropical regions, as a way to rethink nature and landscape with a new rationality. When it comes to his own work, Mendes da Rocha talks about a practice ‘inspired by ideas’ and by ‘man’s ability to transform the place where he lives’, with his eyes on the future. It is a future that can only be found in and by America – a message he has been widely spreading, since the exposure granted by winning the Pritzker Architecture Prize in 2006.

The project that explains best this idea of America is perhaps the Museu Brasileiro de Escultura e Ecologia (Brazilian Museum of Sculpture and Ecology), or MUBE, completed in São Paulo in 1995. The void created under the building’s long beam creates a sense of the ‘new’, focusing on the definition of free space, in contrast to an enclosed building. Here, the human creativity of engineering is used to occupy a territory in a way that tests the boundaries between natural and artificial, always swinging to the latter. Rationality and creativity are the two foundations the American man uses to rebuild the landscape.

0403 sketch croquis ginásio do clube atlético paulistano paulo mendes da rocha architectural review

0404 paulo mendes da rocha atlético paulistano clube architectural review

0402 ginásio do clube atlético paulistano paulo mendes da rocha architectural review

Source: Personal archive of Paulo Mendes da Rocha

Mendes da Rocha and João de Gennaro won the competition for the Ginásio do Clube Atlético Paulistano in 1961

Brasília, the country’s new capital founded in 1960, was expected to teach its generation to value this clearly artificial but human landscape. After the construction of the new capital, a political architectural discourse seemed possible. However, the dictatorship disrupted this idea, transforming those former spaces designed for democracy into places of fear and oppression. The proceeding history of Brazil would confirm the worst fears of that generation – namely the failure of architecture and design to resolve the country’s historical problems, the spatial segregation resulting from the colonial past and the hegemonic presence of the elite in urban spaces, pushing the Brazilian people to the cities’ edges. When drawing an imaginary line between Mendes da Rocha’s first project, the 1958 Ginásio do Clube Atlético Paulistano in São Paulo with João de Gennaro, and one of the latest ones – the Museu dos Coches (National Coach Museum) in Lisbon from 2015, with MMBB and Bak Gordon Arquitectos – one finds a conscious artificiality in the buildings’ tectonic elements, a denial of physical geography under the superior rule of human geography.

Despite Brasília’s apparent misfortune during the years of the dictatorship, Brazilian architects did not lag behind. Some of them dared to fight back, such as João Filgueiras Lima – more commonly known as Lelé – and Mendes da Rocha himself. Even with its contradictions, Brasília stood as testament to the rise of the American World over the Old European World. It was the realisation of the prophecy written in Euclides da Cunha’s 1902 novel Os Sertões: ‘We are condemned to civilisation. Either we progress or we disappear’. From then on, the ambition was to find the means to create a new human geography and the spaces where it could be built.

0401 edifício guaimbê paulo mendes da rocha architectural review

Source: Personal archive of Paulo Mendes da Rocha

Mendes da Rocha and João de Gennaro also designed the Edifício Guaimbê, completed in 1962, which was the first Brutalist apartment block in São Paulo

0303 paulo mendes da rocha raquel gerber architectural review

Source: Personal archive of Paulo Mendes da Rocha / Monade

Mendes da Rocha relaxes at the Casa Gerber with Raquel Gerber, 1973-74

Mendes da Rocha’s postcolonial approach was embodied in the Pinacoteca do Estado in São Paulo, designed with Eduardo Colonelli and Weliton Ricoy Torres and completed in 1998, which transformed a former school of arts into a museum. The simple inversion of the axial structure of the Classical composition, through a new logic of access and internal distribution in the building, subverted the spatial idea usually reproduced in this typology. While in the Pinacoteca this subversion is a gentle one, at Museu dos Coches in Lisbon it is more of an intrusion into the future, a consequence of a manifestly political act.

The Museu dos Coches was a completely new building, designed to house and exhibit the largest international collection of horse-drawn carriages, which was once held by the Portuguese royal family. Also noteworthy is the fact that the Portuguese government specifically asked a Brazilian architect to design a building of strategic importance within the Portuguese cultural and economic framework. It is one of the most visited museums in Portugal, but the construction of the new site was tumultuous. Museologists criticised the decision to build a new space – the former museum was at the old Picadeiro Real (Royal Riding School), next to the National Palace of Belém, the official residence of the Portuguese president.

But among architects, the debate was focused on the approach to the surrounding historical area of Belém. To them, the intuition from the ‘New World’ brought by Mendes da Rocha’s museum seemed to undermine the rough medieval urban fabric, the Royal Palace, the train line, the surrounding gardens and the proximity to the Jerónimos Monastery. The proposal was based on the creation of public spaces unfamiliar to the Mediterranean culture, but which have long been tested within Brazilian architecture, namely since João Vilanova Artigas’s design for the Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism in São Paulo (FAU-USP) at the beginning of the 1960s.

0101 drawing casa butantã paulo mendes da rocha architectural review

Source: Personal archive of Paulo Mendes da Rocha

Casa Butantã (1964) in São Paulo. Mendes da Rocha designed two virtually identical exposed-concrete houses next to each other for himself and his sister

Annettespiro05 mendes

Source: Annette Spiro, courtesy of the personal archive of Paulo Mendes da Rocha

Annettespiro04 mendes

Source: Annette Spiro, courtesy of the personal archive of Paulo Mendes da Rocha

Indeed, everything began for Mendes da Rocha in the 1950s, right before the dictatorship, when he designed the Ginásio Clube, the great value and influence of which he acknowledged when surrounded by students who participated in his homecoming to FAU at the beginning of the 1990s in the aftermath of the dictatorship. This return to school marked the beginning of the clash between post-modern culture and the modern resistance. But, while in Europe and North America this debate was diluted by stylistic concerns, in Brazil it was part of a social and therefore political battle.

There was a strong belief in the ‘ethical superiority’ of the modern language and technique over other visual expressions and building technologies. This conscience, responsible for the resurrection of ‘modern’ values, flourished between some of the FAU’s students who would become Mendes da Rocha’s future team members. They were accompanied by a new generation of promising scholars who openly published their claims in the pages of the Caramelo magazine, founded by the students themselves as a ‘will of Nation’ as Pedro Puntoni wrote in its pages in 1991. It was an attempt to go deeper into politics rather than simply debating architectural questions. Using modern architectural language as a political weapon appeared logical, particularly because it was built on the legacy of Artigas and Mendes da Rocha: ‘The [necessary] transformation is more in a sense of exacerbating and aggravating ideas already said’, Mendes da Rocha wrote in the first issue of Caramelo in 1990.

0603 forma furniture paulo mendes da rocha sketch architectural review

Sketch of the bold and simple lines of the 1987 Loja Forma store in São Paulo

0602 paulo mendes da rocha capela são pedro architectural review

Source: Cristiano Mascaro, courtesy of the personal archive of Paulo Mendes da Rocha

The reinforced-concrete roof of Capela de São Pedro in Campos do Jordão, São Paulo (1987-89) appears to rest on the window frames

0601 paulo mendes da rocha capela são pedro architectural review

Source: Cristiano Mascaro, courtesy of the personal archive of Paulo Mendes da Rocha

Inside Capela de São Pedro concrete beams appear to hover unnervingly

Even if the progressive ways of modern living would not be repeated, they resurged in new discursive contexts. The radical sociability imposed on the inhabitants of the Casa Butantã – finished in 1964 with João de Gennaro – due to an open layout that did not fragment the space, was two decades later overridden by the ingenuity of Casa Gerassi. Here, there was a double social and technological ambiguity: a prefabricated house constructed from a cheap building system finding its place in the noblest neighbourhoods.

Once again, it was an effort to politically transform the public space through almost invisible gestures, but with great symbolic significance. The construction of the Casa Gerassi had a big impact on the upper-middle-class population of the neighbourhood, perplexed by the apparatus on the building site. It was clear proof that the gap between people and the elite could be threatened by a simple construction process. Thus, architecture also took advantage of its constructive performance, as the project seemed to lose some of its political strength after completion and quickly merged with the landscape. Through this approach, Mendes da Rocha tried to overcome the ambiguity that has lingered around Brazilian architects’ work since time immemorial – as noted by Euclides da Cunha, they were condemned to be the most radically modern but mitigated and tamed as a stylistic expression of the dominant social classes. It is a contradiction that has not yet been untangled by the New World; on the contrary, it has only proliferated.

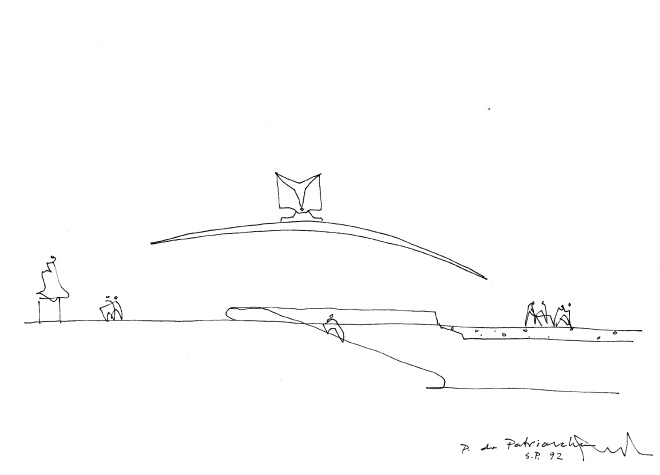

0803 patriarch plaza sketch paulo mendes da rocha architectural review

0801 patriarch plaza paulo mendes da rocha architectural review

Source: Nelson Kon

A cantilevered steel structure shelters a bus station at Patriarch Plaza in São Paulo, part of a revitalisation scheme that took place between 1992 and 2002

0802 pinacoteca paulo mendes da rocha architectural review

Source: Nelson Kon, courtesy of the personal archive of Paulo Mendes da Rocha

The 19th-century Pinacoteca do Estado in São Paulo was renovated by Mendes da Rocha with Eduardo Colonelli and Weliton Ricoy Torres in 1998

It is Mendes da Rocha’s most recent project, SESC 24 de Maio with MMBB, that seems to finally surpass this anachronism. Its cultural and social programme, specifically designed to meet everyone’s needs, regardless of class, salves the architects’ ethical consciousness, free to consider more conceptual thinking about the city. The almost total overhaul of the pre-existing building, reducing its memory to a set of structural artefacts, and coupled with a series of vertical public spaces, adds to the emerging urban condition of the adaptive reuse of existing buildings.

The unique programme of the SESC centre is not repeatable on any other site. In fact, Brazil is the only place where this kind of programme can fully achieve its architectural and political meaning, merging poetry with social intervention. SESC 24 de Maio captures the greatest contribution of contemporary Brazilian architecture, allowing us to finally look in what Vilanova Artigas describes as a ‘safe direction’.

0805 paulo mendes da rocha architectural review all a plan

Source: Joana Mendes da Rocha and Patrícia Rubano

The 2017 documentary It’s All a Plan, directed by his daughter Joana and Patrícia Rubano, charted the life of Mendes da Rocha

Brazilian Pavilion, Osaka Expo, 1970

This vast concrete and steel space-frame, perched delicately on an undulating artificial landscape, was typical of Brazil’s Modernist Paulista School and a crystallisation of Rocha’s belief in architecture as a means of rethinking landscape. With an appearance that belied the temporary nature of the commission it was a hugely successful international debut and, despite campaigning by a local university to keep the structure, it was eventually demolished.

1101 osaka expo pavilion paulo mendes da rocha architectural review

Source: Personal archive of Paulo Mendes da Rocha

1105 osaka expo brazilian pavilion paulo mendes da rocha architectural review

Personal archive of Paulo Mendes da Rocha

1104 osaka paulo mendes da rocha architectural review

Source: Personal archive of Paulo Mendes da Rocha / monade

Museu Brasileiro de Escultura e Ecologia, 1995

Born out of a campaign by the wealthy residents of São Paulo’s Jardins district to prevent the construction of a new shopping mall, the majority of the MuBE was pushed underground to maximise the public space above. Wide steps in the large plaza lead down to the museum’s entrance, crossed by a monolithic concrete ‘table’ that hangs above the site. While the vast cave-like galleries sit below ground, pockets of space above feature gardens designed by Roberto Burle Marx peppered with sculptures.

1205 paulo mendes da rocha mube sketch drawing

1202 paulo mendes da rocha mube architectural review

Source: nelson kon, courtesy of Personal archive of Paulo Mendes da Rocha

1201 paulo mendes da rocha mube architectural review

Source: nelson kon, courtesy of Personal archive of Paulo Mendes da Rocha

Museu dos Coches, 2015

Mendes da Rocha’s first building in Europe, the Museu dos Coches (National Coach Museum) in Lisbon sits on an awkward site, close to the bank of the Tagus River but cut off from it by a railway line. Two lighter steel volumes – one housing exhibition halls and the other admin spaces – sit suspended on large reinforced-concrete foundations and are linked above by a small connecting bridge. A continuation of Mendes da Rocha’s consideration of the museum as a public space, the project is surrounded by a cobbled plaza that wraps around the site, overlooked by a cluster of historic buildings opposite.

0901 paulo mendes da rocha museu coches architectural review

Source: Fernando Guerra / FG+SG

1303 paulo mendes da rocha museu coches architectural review

Source: João Carmo Simões

Lead image: Casa Butantã, coutesy of Nelson Kon

This piece is featured in the AR October issue on Brazil – click here to purchase your copy today

Architectural Review Online and print magazine about international design

Architectural Review Online and print magazine about international design