Major Scream spoilers follow.

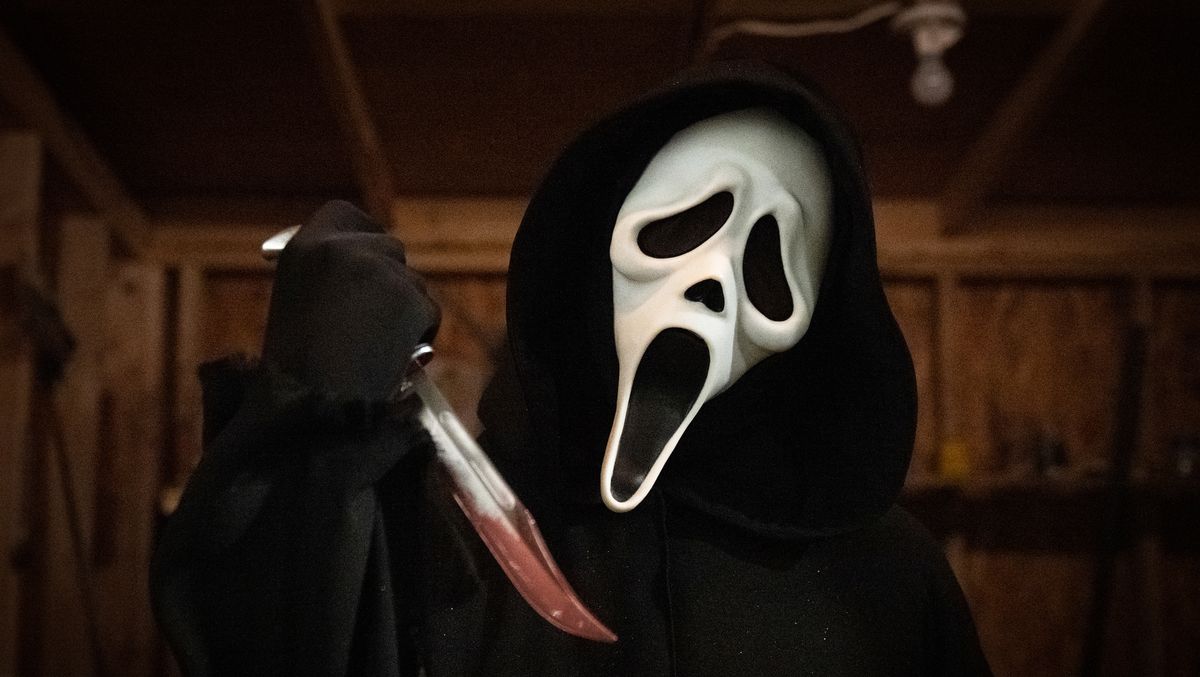

Scream is the ultimate horror whodunit franchise. While others have relied on semi-immortal killers who'd happily crawl out of their own graves before taking a sick day, Wes Craven's metatextual slasher series opted to make the knife-happy Ghostface a mere mantle – taken up by fallible, human killers whose fearsomeness can be swiftly ended by a bullet to the head.

Each Scream movie provides a list of suspects and details their potential motives before systematically wiping them out until the final few survivors, including our unshakeable protagonist Sidney Prescott (Neve Campbell), can deal out cosmic punishment on the guilty parties.

Red herrings are scattered like gingerbread crumbs along the path to resolution. But it's within all these bluffs and double bluffs that the series has been able to toy with its audience's ingrained expectations – asking us to reconsider why exactly we might perceive guilt without justification, or skim over the red flags screaming for our attention.

Does the insular weirdo in love with the popular girl give off a killer vibe? Are we too quick to assume that only a man could be guilty of savage brutality? Self-reflection is in the franchise's very DNA, but this type of commentary – on who kills and is killed – might be at its most effective in the latest instalment, the first since Craven's death in 2015 and minimally titled Scream.

The movie introduces us to Tara (Jenna Ortega) and her teen friends, plus her millennial sister Sam (Melissa Barrera) and Sam's boyfriend Richie (Jack Quaid). The seeds of suspicion are sown – does Mindy (Jasmin Savoy Brown) seem a little too savvy about the rules of the murder game? Does Wes (Dylan Minnette) hide a potentially all-consuming crush?

There's an immediate interest in Sam, who's seen covertly taking antipsychotic medication. The reason? She's trying to banish the hallucinations of her biological father Billy Loomis (Skeet Ulrich), one of the original Ghostface killers.

You'd be forgiven for thinking Scream would cave to the laziest of horror twists and make Sam the killer, after she'd presumably surrendered to the homicidal urges of the voice inside her head. But this is Scream, the king of metatextual horror. It deconstructs tropes, it doesn't replicate them.

Sam not only turns out to be innocent, but she emerges from the chaos stronger and more resilient than before. It's a whole-hearted rejection of centuries' worth of art that equates mental illness and psychiatric disorders with implicit violence. It may not be revolutionary, but it's still beautiful to see from one of the major horror franchises.

These tropes are so embedded in the very fabric of horror that it can feel, at times, like they're impossible to escape.

They were there in 1886, in the dual personalities of Robert Louis Stevenson's Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. They were there in 1909, in DW Griffith's silent short The Maniac Cook, in which a child is thrown into an oven by a man with no soul and no remorse.

They were there in 1920, when The Cabinet of Dr Caligari's protagonist discovered that he was, in fact, a patient at a psychiatric facility whose visions have led him to attack the doctor overseeing his case.

WWII left the world desperately searching for answers as to how the human mind could commit such atrocities. There was a push to label things, to classify conditions. The fantastical monster took a clinical turn when Alfred Hitchcock, who held a lifelong fascination with the work of Sigmund Freud, released Psycho in 1960.

The director may have found both empathy and tragedy in the story of Norman Bates and his tyrannical mother, but the violence he commits is still depicted as a direct manifestation of his dissociative identity disorder (DID).

The decades' worth of copycats that followed were even less kind. We were delivered film after film of bloodthirsty, escaped mental patients – Halloween's Michael Myers, even if he's more bogeyman than man, and Alone in the Dark's quartet of killers, for example – at a time when the shutting of many psychiatric facilities left patients vulnerable and unsupported.

Scream has always poked fun at the idea that horror movies can be blamed for real-world violence, and it would certainly be naïve to place direct blame on the genre for what is a culture-wide demonisation of the mentally ill.

But that doesn't negate, or render unworthy of discussion, the ways horror has helped to maintain such a harmful status quo – one responsible for the fact that, in the US, those with untreated mental illnesses are 16 times more likely to be killed by police.

We can repeat ad nauseam the statistics that prove those with psychiatric disorders are in far more danger of becoming victims of violence than perpetrators of it.

At some point, however, we have to question how much can be done to change the public mindset when the movies and television shows we consume continually portray the direct opposite. A 2017 study conducted by the USC Annenberg Inclusion Initiative found that 46% of characters on film depicted with a mental illness act out in violent ways.

Yes, it's been argued that serial murderers can share certain characteristics associated with antisocial personality disorders like sociopathy, but there is no single unifying profile of the serial killer, and it's particularly wrongheaded to treat any and all other psychiatric disorders as essentially interchangeable.

That kind of dehumanisation is still culturally acceptable enough that even the most egregious examples are rarely met with much collective outrage. 2016's Split featured a villain with DID, played by James McAvoy, who abducts three young women and holds them captive.

The year before, M Night Shyamalan had also put out The Visit, which turned the concept of "sundowning", a state of confusion in those with dementia and Alzheimer's disease triggered in the late afternoon, into an excuse for mayhem and murder.

Part of the difficulty here is that horror offers equally fertile ground for depicting the bodily experience of mental illness in a way that can offer surprising comfort to those familiar with it, and a sense of understanding to those unfamiliar.

It's been a particular topic of interest in recent, less mainstream horror – Tara, in Scream, even names The Babadook as her favourite "scary movie" because of the way it handles motherhood and grief through an externalised, supernatural figure.

Hereditary found ample terror in the ways mental illness can fracture a family unit without turning its characters into monsters, while Rungano Nyoni's I Am Not a Witch followed an eight-year-old with selective mutism who is expelled from her home and sent to live amongst a group of elderly witches.

It’s hardly a new phenomenon, either – from Isabelle Adjani's subway breakdown in Possession to the works of author Shirley Jackson, horror has always been a powerful tool to those wanting to express what it feels like to lose control of your own mind.

These positive and harmful depictions may have always lived side-by-side, but the latter still holds enough cultural power that Sam's psychosis can function effectively as a red herring in Scream. The character spends much of the movie in fear that the identity of her father, and whatever may linger in the coding of her DNA, makes her a danger to others.

The opposite is proven to be true – right when Richie, revealed to be one of the Ghostface killers, attacks her, she sees a hallucination of her father that points her to a knife on the ground and a way to defend herself. Right before she takes out Richie, she delivers one hell of a quip: "I'm introducing a new rule. 'Never f**k with the daughter of a serial killer."

Sure, the sequence as a whole is a touch clunky in its execution, but the image of Sam as the survivor is a potent one.

Scream has never been particularly guilty of the "killer maniac" trope before – the word "psycho" gets thrown around a few times, but those behind the Ghostface mask always have distinct motivations that don't simply stem out of some assumed diagnosis.

But seeing such a forceful rejection of the idea that a disordered brain should automatically be a source of fear and violence feels both refreshing and very in-character for the franchise.

Killers might come and go, but Scream remains as sharp and self-aware as ever.

Scream is out now in cinemas.

![Scream [Blu-ray] Scream [Blu-ray]](https://hips.hearstapps.com/vader-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/1641834230-51KvE-4w42L._SL500_.jpg?crop=1xw:1xh;center,top&resize=980:*)

![Scream trilogy [Blu-ray] [2020] Scream trilogy [Blu-ray] [2020]](https://hips.hearstapps.com/vader-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/1641834282-41l1MwYG8CL._SL500_.jpg?crop=1xw:1xh;center,top&resize=980:*)