Alice Neel, born in 1900, and raised in white, middle-class Pennsylvania, moved to Harlem in New York at the age of 38. She was still recovering from the tragedy of her first marriage, which had seen her first daughter die of diphtheria as a baby, and her second daughter abducted and taken to Cuba by her estranged husband. The shock of those events led to Neel being committed briefly to an asylum. She had two further children, both sons, with whom she lived, most of the time as a single mother, while she tried to make a living from her painting.

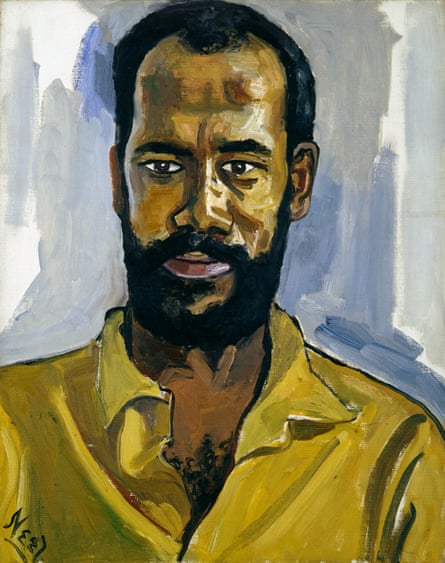

Neel painted what she saw around her: the faces, mostly Hispanic and black, of the community in which she had made her home. It took a long time for her portraits to gain a wider audience. It was not until the late 1960s that she began to be recognised as one of the great American painters of the century, not least because her work offered a unique window on the changing world of Harlem in the years before and during civil rights. (The FBI, which kept her under surveillance as a deviant in the 1950s, denoted her as a “romantic bohemian type communist”). The first retrospective of her work was at the Whitney Museum in 1974, 10 years before her death.

The New Yorker theatre critic and essayist Hilton Als was then 13 or 14. The son of a single mother, and a gay man of colour, Als grew up in Brooklyn, and when he saw Neel’s paintings at the Whitney, he recalls: “I just felt the top of my head blowing off. These were people that I recognised, people whose aura and psychology you felt every day in Manhattan. It was a true picture of urban life.”

More than four decades on, Als felt it was a moment to celebrate that vision of urban life again – all the inclusivity that Neel’s paintings portrayed – at a time when exclusion of all kinds seemed to inform political rhetoric. The show he curated of her portraits, Alice Neel, Uptown , opened at New York’s David Zwirner Gallery in February this year; it comes to London next month.

In America, the exhibition courted controversy on one level. It was still running at a time of heated media argument about “cultural appropriation”, fuelled by the demands of some black artists that a painting by the white artist Dana Schutz, which depicted the mutilated body of Emmett Till, an African American boy lynched in Mississippi in 1955, be removed from the Whitney Museum and destroyed. Als notes how some people “were a bit hesitant at first when it came to Alice. Politically it was a bit charged: they didn’t want to make her a ‘special case’.”

The fact was, he argues, Neel is a special case because she was doing something that was unusual for the time, and is still unusual now. She was a “white woman looking at people of colour”. Als sees the debate around cultural appropriation as misguided. “It feels crazy to me that we should be in a moment where people can be told what they look at and how. When did the oppressed become the oppressor?”

The works Als has chosen for the show make his argument for him. As in Diane Arbus’s photographs, Neel’s paintings reflect a deep need in the painter to connect to humanity beyond herself. “In the contemporary world, artists are almost entirely self-referential,” Als says. “Alice stands apart. She wasn’t a visitor from a bohemian lifestyle downtown, she really lived there. She was very sensitive to the ways people of colour were depicted. None of that ideological junk was in there. She was really looking at the person, their race was another element of what she was representing.”

There was a promiscuity about Neel’s pictures; often her subjects came to her. “People would come and say, you know, ‘I hear you paint Spanish kids’.” Als says. She painted some of the cultural heroes of the Harlem renaissance, but more often the characters and chancers she met on the street. She made a series of portraits of children, and of naked pregnant women – shocking at the time – which were painted with enormous empathy, and a vivid critical eye, but which also seemed to reflect the maternal traumas of her earlier life. She seemed to dramatise a strong kinship with her female sitters in particular, which reminded Als of the fortitude of his own mother when he first saw them, and still reminds him of it now.

“One of the things that comes across with her is that the domestic and the work sphere are combined. She wasn’t financially solvent. She was trying to make work and raise children. The work has discipline – and humility in that she knows it might be years before anyone is interested.”

Above all, though, what emerges is Neel’s connection and love for her subjects. For her, Harlem was never defined by poverty, it seems, but by life. “The fact that it was filled with people,” Als says, “meant it was always filled with hope.”

Alice Neel, Uptown is at Victoria Miro, London N1 from 18 May-29 July

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion