Women like me have been keeping a secret. It’s a secret so shameful that it’s hidden from friends and lovers, so dark that vast amounts of time and money are spent hiding it. It’s not a crime we have committed, it’s a curse: facial hair.

What can be dismissed as trivial is a source of deep anxiety for many women, but that’s what female facial hair is; a series of contradictions. It’s something that’s common yet considered abnormal, natural for one gender and freakish for another. The reality isn’t quite so clearcut. Merran Toerien, who wrote her PhD on the removal of female body hair, explained “biologically the boundary lines on body hair between masculinity and femininity are much more blurred than we make them seem”.

The removal of facial hair is just as paradoxical – the pressure to do it is recognized by many women as a stupid social norm and yet they strictly follow it. Because these little whiskers represent the most basic rules of the patriarchy – to ignore them is to jeopardize your reputation, even your dignity.

About one in 14 women have hirsutism, a condition where “excessive” hair appears in a male pattern on women’s bodies. But plenty more women who don’t come close to that benchmark of “excessive” still feel deeply uncomfortable about their body hair. If you’re unsure whether your hair growth qualifies as “excessive” for a woman, there’s a measurement tool that some men have developed for you.

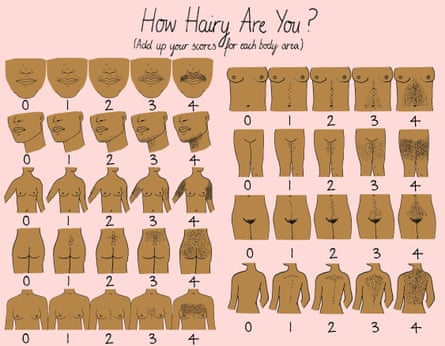

In 1961, an endocrinologist named Dr David Ferriman and a graduate student published a study on the “clinical assessment of body hair growth in women”. More specifically, they were interested in terminal hairs (ones that are coarser, darker and at least 0.5cm/0.2 inches in length) rather than the fine vellus hairs. The men looked at 11 body areas on women, rating the hair from zero (no hairs) to four (extensive hairs). The Ferriman-Gallwey scale was born.

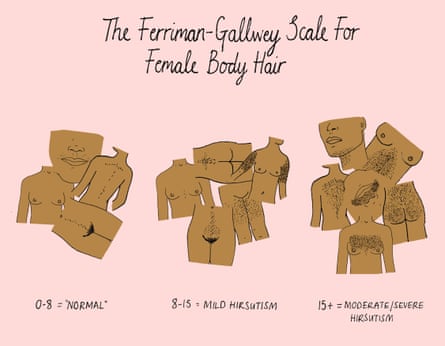

It has since been simplified, scoring just nine body areas (upper lip, chin, chest, upper stomach, lower stomach, upper arms, upper legs, upper back and lower back). The total score is then added up – less than eight is considered normal, a score of eight to 15 indicates mild hirsutism and a score greater than 15 moderate or severe hirsutism.

Illustration: Mona Chalabi Photograph: Mona Chalabi

Illustration: Mona Chalabi Photograph: Mona Chalabi

Most women who live with facial hair don’t refer to the Ferriman-Gallwey scale before deciding they have a problem. Since starting to research hirsutism, I’ve received over a hundred emails from women describing their experiences discovering, and living with, facial hair. Their stories loudly echo one another.

Because terminal hairs start to appear on girls around the age of eight, the experiences start young. Alicia, 38, in Indiana wrote, “kids in my class would be like, ‘Haha look at this gorilla!’”, Lara was nicknamed “monkey” by her classmates while Mina in San Diego was called “sasquatch”. For some girls, this bullying (more often by boys) was their first realization that they had facial hair and that the facial hair was somehow “wrong”. Next, came efforts to “fix” themselves.

Génesis, a 24-year-old woman described her first memories of hair removal. “In fourth grade, a boy called me a werewolf when he saw my arm hairs and upper lip hairs … I cried to my mom about it … she bleached my lower legs, my arms, my back, my upper lip and part of my cheeks to diminish my growing sideburns. I remember it itched and burned.”

After those first attempts come many, many more – each with their own investment in time, money and physical pain. The removal doesn’t just make unwanted hair go away, it raises a whole new set of problems, particularly for women of color. Non-white skin is more likely to scar as a result of trying to remove hair.

Instead of reading or finishing homework on the car drives to school growing up, I would spend the entire length of the drive obsessively plucking and threading my mustache. Every day. – Rona K Akbari, 21, Brooklyn

On average, women with facial hair spend 104 minutes a week managing it, according to a 2006 British study. Two-thirds of the women in the study said they continually check their facial hair in mirrors and three-quarters said they continually check by touching it.

The study found facial hair takes an emotional toll. Forty percent said they felt uncomfortable in social situations, 75% reported clinical levels of anxiety. Overall, they said that they had a good quality of life, but tended to give low scores when it came to their social lives and relationships. All of this pain despite the fact that, for the most part, women’s facial hair is entirely normal.

If I know I have visible facial hair, I’m much more reserved in social situations. I try to cover it up by placing my hand on my chin or over my mouth. And I’m thinking about it constantly. – Ashley D’Arcy, 26

Meanwhile, my 95-year-old demented, deaf and blind Italian aunt sits in a nursing home, and whenever I visit, she points to and rubs her chin, which is her way of communicating to take care of the hair situation. That’s how I know she’s still in there and she cares. I hope someone returns the favor in 40 years. – Julia, 54

There are, however, some medical conditions which can cause moderate or severe hirsutism, the most likely of which is polycystic ovary syndrome, or PCOS, which accounts for 72-82% of all cases. PCOS is a hormonal disorder affecting between eight and 20% of women worldwide. There are other causes too, such as idiopathic hyperandrogenemia, a condition where women have excessive levels of male hormones like testosterone, which explains another 6-15% of cases. .

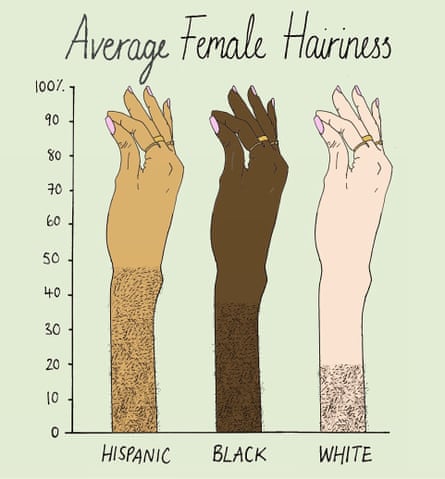

But many women who don’t have hirsutism, who don’t have any medical condition whatsoever, consider their hairs “excessive” all the same. And that’s much more likely if you’re a woman of color.

The original Ferriman-Gallwey study, like so much western medical research at the time, produced findings that might not apply to women of color (the averages were based on evaluations of 60 white women). More recent research has suggested that was a big flaw, because race does make a big difference to the chances that a woman will have facial hair.

In 2014, researchers looked at high-resolution photos of 2,895 women’s faces. They found that, on average, the white women had less hair than any other race and Asian women had the most. But ethnicity mattered too – for example, the white Italian women in the study had more hair than the white British women.

But more than a gender thing, for me my hair was about race/ethnicity. My hairiness really solidified how different I was from my peers. I grew up in the suburbs of Dallas. And although my school was pretty diverse, the dominant beauty norm was to be blonde and white. – Mitra Kaboli, 30, Brooklyn

These numbers might be helpful to women like Melissa who said her facial hair meant “I felt inferior, I was a ‘dirty ethnic’ girl”.

But giving reassurance to ethnic minorities probably isn’t why this research was undertaken. The study was funded by Procter & Gamble, the consumer goods company worth $230bn which sells, among other things, razors for women. They know that female hair removal is big business.

Over the years, as women showed more of our bodies – as stockings became sheer and sleeves became short, there was pressure for these new exposed parts to be hairless. Beginning in 1915, advertisements in magazines like Harper’s Bazaar began referring to hair removal for women. Last year, the hair removal industry in the US alone was valued at $990m. The business model only works if we hate our hair and want to remove it or render it invisible with bleach (a norm just as unrealistic as hairlessness – brown women rarely have blonde hair).

When did we sign up to an ideal of female hairlessness? The short answer is: women have hated our facial hair for as long as men have been studying it. In 1575, the Spanish physician Juan Huarte wrote: “Of course, the woman who has much body and facial hair (being of a more hot and dry nature) is also intelligent but disagreeable and argumentative, muscular, ugly, has a deep voice and frequent infertility problems.”

These signposts are strictest when it comes to our faces, and they extend beyond gender to sexuality too. According to Huarte, masculine women, feminine men and homosexuals were originally supposed to be born of the opposite sex. Facial hair is one important way to understand these distinctions between “normal” and “abnormal”, and then police those boundaries.

Scientists have turned their sexist and homophobic expectations of body hair to racist ones, too. After Darwin’s 1871 book Descent of Man was published, male scientists began to obsess over racial hair types as an indication of primitiveness. One study, published in 1893, looked for insanity in 271 white women and found that women who were insane were more likely to have facial hair, resembling those of the “inferior races”.

These aren’t separate ideas because race and gender overlap – black is portrayed in mass media as a masculine race, Asian as feminine. Ashley Reese, 27, wrote “part of my self-consciousness about my facial hair might also tie into some ridiculous internalized racism about black women being less inherently feminine”. While Katherine Parker, 44, wrote, “It makes me feel very confused about my gender.”Some women are pushing back. Queer women – those who are questioning heterosexual and cisgender norms – are already thinking outside of the framework that shames female facial hair. Melanie, a 28-year-old woman in Chicago explained that as a queer woman “there is less of a prescription for what I should embody as a woman, what attraction between my partner and I looks like, which has helped immensely in coming to terms with my facial hair”.

Social media accounts like hirsute and cute, happy and hairy and activists like Harnaam Kaur are resisting these norms too, by shamelessly sharing images of hairy female bodies. And even women who aren’t rejecting these standards outright, feel deeply ambivalent about them. “I understand, on a rational level, how inherently misogynistic it is to expect women to be constantly ripping hair out of themselves, hair that grows naturally, wrote one woman who, like many I heard from, asked to remain anonymous. “But I can’t bring myself to accept it and let it grow.”

Another wrote: “It’s one thing to be a little heavy, or short, or both. But facial hair? That’s pushing it.”

I’m not about to judge any woman for removing her facial hair. Despite knowing that I don’t need “help”, I still go to see a beauty “therapist” each month. I pay huge sums so she can zap me with a laser that damages my hair follicles. I’ve signed up for a solution, even though I know that the problem doesn’t really exist. I lie there wincing with each shock as she asks me about my weekend and says “Honey, are you sure you don’t want me to do your arms too? They’re very hairy.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion