When Oliver Postgate, the late maestro of children’s television programmes, first invited young viewers to travel with him “in our imaginations across the vast starry stretches of outer space”, he was introducing many of them to a lifeform they would never forget: the Clanger.

These little pink, knitted, nozzle-nosed aliens, Postgate suggested, were really rather like us, living out their lives on the “small planet wrapped in clouds” they called home. Now it has emerged they were much more like us than we thought.

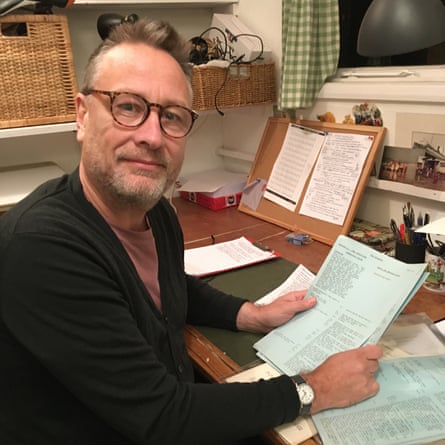

A new book put together by Postgate’s son, Daniel, is to make public the full scripts of the puzzling show for the first time and to confirm a rumour often dismissed as heresy: yes, the Clangers did use the odd profanity and actually spoke a language that was very close to our own. The strange swanee-whistle voices that entertained millions of children on the BBC show in the 1970s were actually noted down in a full and detailed screenplay, written out in English.

“People have often wondered whether there was swearing,” said Postgate, who revived the show for a new generation in 2015. He is surprised, he said, by the idea the soundtrack of whistles could ever have been entirely improvised. “Some people don’t realise that the scripts were written in English. And those who do often speculate on whether a certain amount of bad language – swearing, to be blunt – had been slipped into their conversations.”

The magical, intergalactic introduction to the show, written and voiced by Postgate, went on to draw viewers in “very close”, suggesting that they “look and listen very carefully”. Those children who did just that may well have noticed that the show’s fictional location, a “calm serene orb”, was inhabited by beings with a short temper.

“It was a very much a 70s family,” said the Clanger creator’s son. “So they were a bit abrasive with each other. Nothing really bad, but you can’t get away with that so much now.”

Those voicing the Clangers may not have used immersive acting techniques like the Method to get into character, but they did have to know what was being expressed.

“Now fans of the show can look and see exactly what my dad had written for the Clangers to say. After all, you can’t just whistle away in any old nonsense. The whistlers have to know their motivation.”

In addition, Postgate explained to the Observer, the more volatile dialogue for the Soup Dragon was also written down in the script by his father. The sounds made by the enigmatic Iron Chicken, however, were simply indicated by tone. “The Iron Chicken was more emotive. So they were either plaintive noises or enthusiastic.”

Clangers: The Complete Scripts 1969 to 1974 is being published by the crowdfunded publishing house Unbound, and contains 27 scripts, alongside Oliver Postgate’s special musical notation for each episode. It also reproduces many of the original illustrations created by Postgate’s collaborator, Peter Firmin, and several sketches showing the evolution of the unique creatures on the show, including the Soup Dragon and the Froglets. It even reprints the knitting patterns for the original Clanger characters’ models.

Postgate senior, who died in 2008, was also behind popular children’s shows Pogles’ Wood, Noggin the Nog, Ivor the Engine and Bagpuss. He once said in an interview that Major Clanger, when confronted with a door that would not open in an early episode, can be heard whistling the words: “Sod it, the bloody thing has stuck again.” At the time it was unclear if Postgate was merely teasing his audience, especially as he added that the nicer child would be more likely to hear the line as: “Oh dear, the silly thing’s not working properly.” The newly published scripts make it clear the ruder version was on the money.

“My dad’s original intention was for the series to be shown without narration, so it would be left up to the viewer to decide what the Clangers were saying,” said Postgate. “Indeed, when Clangers was shown at a festival in Germany, he asked a German producer whether he could follow the story. ‘Of course! They are speaking perfect German!’ the producer said.”

The book also details a minor Postgate scandal surrounding the Pogles. “I have included some new documents in the book that show how my dad and Peter presented their ideas. At first the BBC were quite casual and laissez-faire about what they did. Then they introduced the Pogle Witch and some children were terrified. After that the BBC wanted to be clear exactly what they were going to do. In effect, the Pogle Witch was banned.”

Postgate also suspects his father drew on some intriguing sources in the show: “The series came out shortly after the release of David Bowie’s Space Oddity album. And clearly, space was in the air in those days, what with the lunar landings. It was a creative touchstone.”

The family’s political legacy was also an inspiration. “My dad came from a strong socialist heritage,” said Postgate. “His grandfather was the Labour MP George Lansbury. Lansbury’s philosophy had a lasting influence and I think it’s apparent in his stories.”

The Clangers were briefly drawn into this combative arena in a special one-off episode called Vote for Froglet, in which Postgate tried to persuade the planet’s residents of the virtues of the two-party system. After a snap election, with the Soup Dragon running on the “free soup for all” ticket, the Clangers were unconvinced and stuck with their enlightened autonomous collective.

And what of that powerful opening sequence, with the camera tracking across the cosmos? Well, Postgate believes his father may have been inspired by the footage that opens one of Britain’s most celebrated films, Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s A Matter of Life and Death. “I often wonder if he consciously reused the images and ideas that open that film. I would not be surprised. He shared a lot of Powell and Pressburger’s vision of Englishness – the pastoral idealism.”