This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

In June 1982, Stephen Sondheim, still reeling from the flameout of the original Broadway production of Merrily We Roll Along seven months earlier, had his first meeting with the Off Broadway playwright and director James Lapine. The future collaborators soon were comparing their tastes not just in plays but in movies, Sondheim’s greatest cultural passion after music. Lapine had recently seen and liked The Exterminating Angel, the 1962 classic by the Spanish Mexican director Luis Buñuel. Sondheim was a fan of Buñuel’s 1972 The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie. Lapine thought it might be a possible project. They set up a screening, but nothing came of it. When they reconvened at Sondheim’s Turtle Bay townhouse after Labor Day, Lapine arrived with a bunch of random images to see if they might strike any creative sparks. The last in the pile was a postcard of Georges Seurat’s A Sunday on La Grande Jatte — 1884. It inspired a torrent of riffing, and a week later Lapine brought Sondheim the first five pages of what would become Sunday in the Park With George.

This fall, Here We Are, Sondheim’s musical adaptation of both Discreet Charm and Exterminating Angel, written with the playwright David Ives, will have its premiere — more than four decades after Lapine floated the notion of a Buñuel musical, a decade after Sondheim and Ives started serious work on it, and nearly two years after Sondheim’s death late Thanksgiving Night in 2021. That Sondheim had left behind a full show came as a shock even to many in his circle. He often talked about his frustration with the project’s slow progress as the months and then years piled up and he headed toward his tenth decade. In the spring of 2017, he sent me a video of a workshop of its first act led by Kelli O’Hara and Steven Pasquale, asking for my thoughts. That fragment was intriguing as far as it went, but he was unsure of what would come next. After that, the show, known by the placeholder rubric Buñuel, never seemed to move forward or even settle on a title.

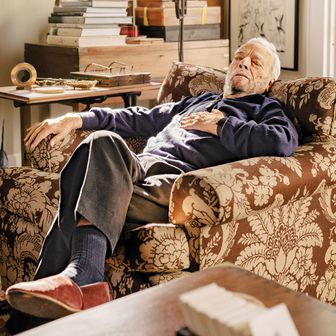

This was nothing new for Steve, who was congenitally behind on his work and loved kvetching anxiously about it, always with acutely self-mocking humor. Before Buñuel, he’d been plenty tardy in finishing the critical and autobiographical essays that formed the spine of his two magisterial volumes of collected lyrics. And what was the rush, anyway? Who thought he would die anytime soon? Not me, and not many others who knew him. Yes, he was 91 at the end, but he wasn’t ill and had ducked COVID by retreating with his husband, Jeff Romley, to their second home in Roxbury, Connecticut. Steve remained as sharp, curious, and playful as ever. My last phone conversation with him the weekend before his death was typical. After savoring in giddy detail the just-opened Classic Stage revival of Assassins, he let loose with a new anecdote about the most notoriously exasperating of his Broadway collaborators, the West Side Story and Gypsy librettist Arthur Laurents (he knew I was a ready audience for Arthur horror stories), then invited me to join him that Wednesday to see two new American plays running in repertory on Broadway. The doubleheader was tempting, but I was on my way to a family Thanksgiving in California. So we looked forward instead to a dinner I’d set up for after the holidays in New York, where he could finally meet one of his all-time favorite actors, Harriet Walter, whom I’d come to know professionally and who would be visiting from her home in England.

When Steve’s lawyer and friend Rick Pappas called me in Los Angeles before dawn early Friday morning to deliver the devastating news, it caught me completely off guard, as it did so many others. I couldn’t digest it. I had first met Steve 50 years earlier, when I was a senior in college. I had heard and seen and admired his work my entire sentient life. He was a paternal figure for me, as for countless others he had mentored, counseled, and taught.

On that black Friday morning, I distracted myself by helping Rick alert the press to Steve’s death. Steve had been a palpable presence at the two shows he had running then (a revival of Company as well as Assassins), both of which had holiday matinees that afternoon. The goal was to pause the announcement so the casts could be told the news in person after the curtain fell rather than learn it in the wings mid-performance from Twitter. Steve’s colleagues on the Steven Spielberg film of West Side Story, gathering for its imminent world premiere, also had to be notified.

The secret held until the end of the day New York time. Once the news was out, I could no longer duck the reality and magnitude of the loss. It was many months before I could listen to Steve’s scores again or see a production of his shows without being overwhelmed by grief. It took the catharsis of Maria Friedman’s production of Merrily at the New York Theatre Workshop a year after Steve died — by far the most successful realization of the show he and his librettist George Furth had revised for years after its Broadway stillbirth — to get me to start reconnecting to all the riches he left behind.

Earlier this year, as another exhilarating Sondheim revival, Thomas Kail’s staging of Sweeney Todd, was heading into production on Broadway, Rick called me with the surprising news that weeks before his death, Steve had authorized Buñuel for potential production. Rick asked if I might help him, David, and Joe Mantello, the director who joined the project in 2016 and became central to its development, tell the story of its often tortured path to completion. I read the latest version of the script, heard a demo rendering of the score (with all the roles sung by the show’s musical director, Alexander Gemignani), and immersed myself in David and Joe’s intimate recollections of how Steve persisted in his art despite the obstacles of self-doubt, aging, and the isolation inflicted by a pandemic whose fallout mirrored aspects of the surreal Buñuel movies that had captured his imagination as a young man.

What follows is an edited transcript of those conversations, which took place this summer ahead of rehearsals for a September 28 first preview at the Shed in Hudson Yards. David and Joe also shared some contemporaneous emails about the show’s progress (or lack of it). As we talked, we found ourselves not just examining the creation of Steve’s final work but also looking back, perhaps with a little perspective now, on what this remarkable artist and person meant to the theater and to those of us who knew him and loved him.

Frank Rich: David, you first started working with Steve several years before Joe. How did you and Steve begin your collaboration?

David Ives: Steve called me up in December of 2009 and asked me over for a drink. We sat and we drank and we chatted, and finally I said to him, “Steve, you said you wanted to talk about something, and you said it wasn’t important.” He said, “Did I say that?” I said, “Yes you did.” And he said, “Well, I have this idea for a musical and I wondered if you wanted to work on it.” And what do you say to Stephen Sondheim when he says that? I said, “Great. What’s the idea?” So he tells me, and I said, “I like that idea.” And he said, “Well, I’m glad you say that because I’ve been taking some notes.” And he reached behind a pillow of his couch and he took out this manila envelope. He said, “Just tell me what you think if you don’t like them.” They were extraordinary, five or six pages of his thoughts and reflections about what the show could be.

Joe Mantello: Being summoned to his house is terrifying. But what you are greeted with is actually someone who is very open and curious and eager to have collaborators. With Assassins, I was a director who at that point hadn’t really directed a musical, and I had some ideas to present to John and Steve about how I wanted to do it. I went to Steve’s townhouse, and it’s intimidating. There he is, and you’re this guy who’s going to come in and say, “This is what I think your musical needs.” One thing I talked about was combining the roles of the Balladeer and Lee Harvey Oswald. And he listened very, very patiently and said, “I don’t think that will work for the following reasons,” and then he enumerated those reasons. But he said, “You are the director, and you have to pursue that.” That’s a great collaborator to me.

FR: David, Steve’s initial idea for you was not Buñuel.

DI: It was this musical called All Together Now, which I think he had pitched to various playwrights over the years. He wanted a musical that exploded a single moment in the lives of two people meeting for the first time. We’d see the moment without music and then we’d explore it musically. That would happen through other characters Steve called “the Selves,” the inner selves of the man and woman. A great idea, but this is Steve, so of course it was complicated. We went to work on it almost immediately.

FR: Were there ever any songs for All Together Now?

DI: He wrote two versions of one song, as far as I know, and I thought it was a terrific song, but he was getting lost in the theme-and-variations puzzle of it and couldn’t find his way forward.

IVES AND SONDHEIM abandoned All Together Now in August 2013 after they learned a new, if short-lived, Broadway musical, First Date, had an overlapping premise. Around that time, Sondheim and Ives began to work in earnest on Buñuel. Sondheim had started talking about reviving the idea a couple of years earlier, and in 2012, the artistic director of the Public Theater, Oskar Eustis, who had produced a revision of Sondheim’s previous musical, Road Show, in 2008, joined Rick Pappas in a lengthy effort to secure the underlying rights from the estates of Buñuel and the films’ screenwriters.

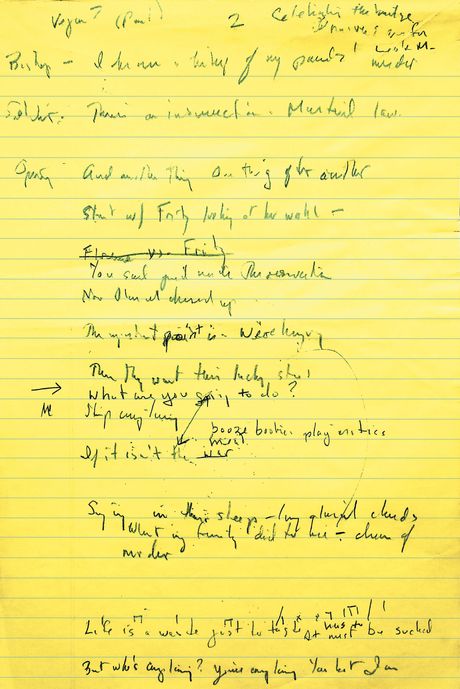

DI: I went over to Steve’s house, and we watched both movies. We talked about them, we took notes, we started brainstorming, and I think that we had a very good idea from pretty early on about the shape of this thing. The first act would be Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie; the second act would basically be Exterminating Angel.

FR: Can you explain for the uninitiated what Buñuel and his movies are about?

DI: Luis Buñuel, Spanish director, Surrealist tradition, friend and collaborator of Dalí. He was a bit like Steve. Brilliant, unorthodox, a huge variety in his work over the years. Discreet Charm is about a circle of six colorful upper-middle-class French friends who are continually in search of food — supper, a cup of coffee, whatever — but continually get stymied trying to find it. Exterminating Angel is radically different. Very severe. It’s again about a circle of society friends. This time, the group is in a mansion and they can’t get out of the fancy room they’re in. So they spend the movie “trapped,” even though all they have to do is walk out the open door. Steve and I merged the two movies and made it the same set of friends all the way through.

FR: You decided not to set it in France or Mexico.

DI: At first it was going to be set in France. But we came to the idea that nobody would care. Bad enough that these people have money, but they have to be French? That is loading a show with absolutely too much baggage. Setting it in America seemed an obvious way to go. We had a very good idea of the characters. A lively billionaire hedge-fund type. His wife, a society interior decorator. Her kid sister, a kind of out-there East Village lefty. And the friends who go looking for food with them. A charming Casanova who’s the ambassador of a tiny corrupt Mediterranean duchy. A ballsy talent agent, very smart, very loud, always on the phone. A cosmetic surgeon for people who don’t need cosmetic surgery but get it anyway. A hapless colonel from Homeland Security and a bishop who’s going door-to-door trying to find a better job because he’s such a lousy priest. A very beautiful, very complicated young soldier who’s our love interest. Or is he? Plus the ultimate Merchant-Ivory butler. Or is he? A mysterious maid. Characters end up being stuck in the room with each other and getting to know each other. The rich have to undergo what only the poor know, which is to say, deprivation, hunger, lack of water, lack of space.

JM: It’s about a lot of things. Distraction and what happens when you have privilege and unlimited choices and then those choices go away. What do you have to face when you look in the mirror? I come back to Buñuel’s note when asked to prepare audiences for The Exterminating Angel: “The best explanation for The Exterminating Angel is that, rationally, there is none.” The second act is the exact opposite of the first act. This show essentially starts with movement on a road from place to place in search of a meal and the first act ends with them achieving their goal and they get a meal. The second act is the inverse. It starts after they’ve had the meal and now they’re stuck and how do they get back on the road? Steve’s love of puzzles is so well known.

FR: At the top of the second act of Sunday, of course, the characters can’t break out of Seurat’s painting. Lapine had to create a whole new story and yank them out of that century entirely if they were to move on. Here, the tone feels darker. They are truly trapped. You feel that the world is ending, that mortality looms. And yet the show is haunted still by that intense feeling of yearning, a wistfulness, that’s so moving in Steve’s work, embodied this time in a repeated lyric for the ensemble: “Buy this perfect day / Put it on display / Let it stay / Just this way / Forever.”

DI: Steve being Steve, he was smart enough to see there was an opportunity there for doing two things at the same time, which is to say the joy of “Buy this perfect day” and then “Let it stay just this way forever,” which is what happens in Act Two.

IVES AND SONDHEIM were off to a fast start, meeting every week or two at Sondheim’s townhouse to brainstorm. He started writing music early on.

DI: The first thing Steve played for me was a vamp that recurs throughout the show. And how my heart leapt up the afternoon he played it for me. Steve always wrote fantastic vamps, and this was classic Sondheim. Ba-dum-bum bummmm, with these interesting harmonies leading to a gorgeous button. Maurice Ravel would be proud of it, but so would Arnold Schoenberg and Gershwin. But it’s recognizably Steve’s voice, that musical language of his we know so well.

A FIRST READING WAS held in January 2016 during off hours at the bar at the Public with a pickup cast.

DI: Then skip to when Joe entered the picture. He came in and had all kinds of wonderful ideas. We would meet in Steve’s house, or we would exchange emails. I would summarize our conversations in notes, which I then would send to Joe and to Steve and me, and that was how we collaborated for a long time.

AT FIRST IT WAS full speed ahead.

An email exchange in September 2016:

From: Joe Mantello

To: David ives

David —

Yesterday was absolutely thrilling. I feel — no, I know — we have the makings of something remarkable here. You’re already well on your way.

I found an Albee quote about A DELICATE BALANCE that might be useful on … uh, well … what are we calling this??????

“The play concerns … the rigidity and ultimate paralysis which afflicts those who settle in too easily, waking up one day to discover that all the choices they have avoided no longer give them any freedom of choice, and that what choices they do have left are beside the point.”

I want to dive in on the script this week and try to put a few detailed thoughts down for you to ponder.

Best,

Joe

From: David Ives

To: Joe Mantello

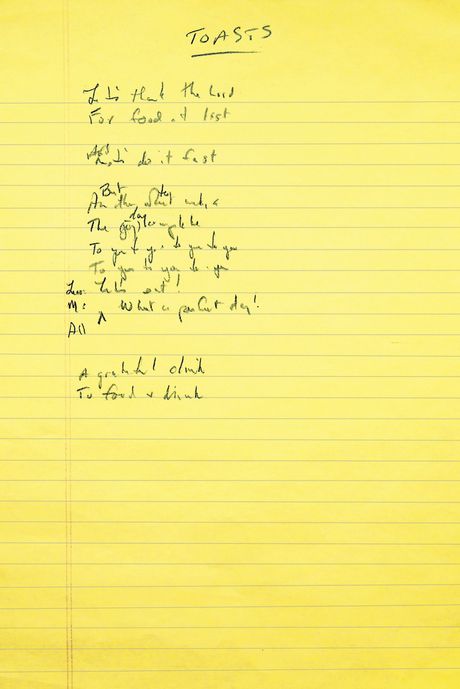

Here are the notes. And by the way, we have no title for this baby. Some earlier not-very-good discarded suggestions:

“Bon Appetit.” “Square One.” “Charm.” “Let’s Eat!” Or we could just call it “Don’t Be Absurd.”

D.

JM: As usual, Steve was experimenting with musical structure. The six protagonists almost always sing as a group while the solos are given to characters they meet along the way. There’s an unconventional, almost counterintuitive, approach to the score.

DI: I think that what Steve loved about Discreet Charm was the road sequences: As we follow this group of very tony friends looking for a meal, the movie cuts away, without explanation, to them walking down a country road in beautiful sunshine with birds twittering in the background. And we just hear the sound of their footsteps. We see them walking, and walking, and walking, not talking, not relating to each other, just heading down this road. The movie probably does that three or four times. Obviously, this is Surrealism that we’re in, and it’s such a rich metaphor. But it was a conceptual challenge. Early on I was asking Steve, “Are these silent interludes, and how do we keep the audience’s interest? Is there music? What is happening in those interludes?” He wanted to begin the show with them on the road for a very long time. I spent a lot of time trying to talk him out of that because, I said, “Those sequences work in the movie because we’ve seen these characters, and to cut away to them on the road suddenly is an interjection of something mysterious. But you can’t begin with mystery if you haven’t established the world that we’re in.” He tried writing a road sequence at the beginning of the show. That was part of the big discussions early on in the show’s gestation. And, of course, the road became a directorial and production challenge.

JM: The practical concern that I had was they go to three different restaurants and within a couple of lines they’re back on that road. To find an elegant solution that doesn’t involve winches and things coming on and off really dictated the design of the first act. It was a thrilling process to go through, but it was a really difficult set to design.

DI: In the end, as I’d hoped, we didn’t start the show with the road. Instead, we set the characters up in an opening scene and only then moved them onto the road. After that, the first act alternates between restaurant scenes and road scenes. In an old-fashioned musical, the road would have been a so-called in-one scene. The curtain would have come down and the road would have been played in front of it while the set changed to a new location. But Joe and David Zinn found a brilliant way for us to move on and off the road without doing that. Modern theater magic.

BUT THE WORK hit a trouble spot in late 2016.

DI: When I had begun working with Steve, I had a drink with Lapine and said, “Can you give me any advice?” He said, “You have to give him a deadline.” And that really worked for Lapine — though he also said that Sondheim once asked him, “You want it Tuesday or do you want it good?” The problem is that I am not made like Lapine at all. I went to Catholic school, I did my homework, I figured everybody else did theirs. I am not the sort of person to say to anybody, Sondheim or anybody else, “I’m coming over to your house on Saturday and you have to have a song.” That is not me. That’s why it was helpful when Joe came on the project because Joe energized Steve. But I don’t think there was anybody who could really get him to work.

An email exchange on December 15, 2016:

From: Stephen Sondheim

To: Joe Mantello

Joe —

David and I are having something of an existential crisis about the show. We’re not sure how to go ahead: every path and procedure at the moment seems arbitrary, and much of what we’ve written feels superficial to us. I could go into more detail here, but what we’d rather do is set up a meeting with you next week and talk about our fears and stagnation. Would that be possible?

Steve

From: Joe Mantello

To: Stephen Sondheim

Steve —

I’m so sorry to hear this, and — of course — I’d be happy to meet and see if we can find some sort of solution. For my part, I left the reading even more invigorated and inspired about the possibilities.

But — then again — I don’t have to write it.

Joe

JM: We met a week later at Steve’s house for a meeting called to discuss the “existential crisis.” Steve and David’s concerns were discussed, as were possible solutions, and by the end of the meeting everything seemed back on track. In my experience, this kind of crisis of confidence is fairly typical.

BUT FORWARD movement remained slow.

JM: Ideally, musicals get written in a room together; that’s the best of all possible worlds. Steve had a process that involved doing little experiments that he would keep to himself until he felt that he had something to share with us. Meanwhile, we would either tread water or David and I would go back and comb through a draft and try to make it richer and deeper. Oftentimes, we would be waiting for him to have something to show us. I mean, I don’t think I’m telling tales out of school. He was a world-class procrastinator.

FR: He was the first one to say it about himself. His procrastination was legendary.

JM: At one point, I said to David about the endless search for a title I thought we should call this The Dog Ate My Homework.

DI: Steve once used an ingrown toenail as the reason why he was unable to work in the past few days. In fact, he spent a good deal of time instructing me in how to cut your toenails correctly so that you avoid ingrown toenails.

AT THE APRIL 2017 reading of the first act with Kelli O’Hara and Steven Pasquale, the score was sung. But Sondheim’s pace was slow the rest of that year and the next.

An email exchange in December 2017:

From: Stephen Sondheim

To: Joe Mantello

Hi, Joe —

Hope things are going smoothly. I didn’t want to interrupt, but David thought I should send you the opening section of Act II, which is now polished enough to be respectable. More will be soon. Anyway, here it is.

Steve

From: Joe Mantello

To: Stephen Sondheim

Hello Steve, This looks wonderful. Eager to hear it.

I’m heading back to NY today — after 6 long weeks away. Let me know if you need anything.

J

From: Stephen Sondheim

To: Joe Mantello

A rhyme for bourgeois …

DI: Then the trail of work goes dry until he seems to have really gone to work hard for some reason in August 2018. He sent me several pieces of work that month. Then there’s really nothing written from him for quite a while.

An email exchange on January 11, 2019:

From: Stephen Sondheim

To: Joe Mantello, David Ives

My deepest apologies for the delay and for discombobulating your schedules. I’m having extreme difficulty in writing, due partly to the intractabilities of the piece and partly to age slowdown. It’s entirely my fault, not David’s.

I’m not working on anything else, so I’ll slog ahead as best I can and hope to have it finished this year in time for our moving forward next.

Meanwhile, Happy New Year.

Steve

DI: Steve had slowed down quite a bit on the show. I felt that I could be at fault. We were great friends through all of this, so I said to him frankly, “I wonder if you wouldn’t do better if you brought somebody else in with some fresh ideas.” He was perfectly fine with that thought. I thought it was for the best of the piece, which was fascinating, but I wondered if I was, in some way, not helping him forward. So I was away from it for a time.

IVES OFFICIALLY WITHDREW from Buñuel in an email on April 5, 2019. Sondheim enlisted his friend Jeremy Sams, a British director, composer, and librettist, to join him to work on the project at his Connecticut home that May and June. The collaboration didn’t produce results, and in October 2019, Ives returned to the project.

DI: Suddenly Steve called me up and he said, “You know, I’ve just had a great idea. Let’s go back to All Together Now.” I didn’t know where that was coming from, but he was all on fire about it. I went over and we talked about it and it was great. It looked like he was going to go back to work, but it just fizzled out and we were back to Buñuel.

JM: Very little work is done on Buñuel in the several months between David’s return and late 2019. The email trail goes cold.

SONDHEIM BY THEN had decided against seeking a renewal of the underlying rights to the Buñuel films.

DI: 2020 was a fairly dark time for this musical. My work was done in a way. I don’t remember writing much on it. It was really downtime, and I mean down in every sense of the word.

JM: I got an email or a phone call from Steve saying that he just couldn’t crack Act Two. He’d written up to a certain point, and he felt like he couldn’t crack it, and he said that, regrettably, he was going to set it aside. I don’t know if the word abandon was used, but he was going to set it aside. Then we were all walloped by the pandemic and we retreated into our homes and it was very quiet for a long time.

FR: The substance of the show — notably a second act when no one can leave a room — was well in place when COVID fell out of the sky in March of 2020 and trapped us all in rooms. How weird that must have been, particularly since it happened after work on Buñuel had been abandoned. Did you ask yourselves, “What the hell, did we write some sort of prophecy of what’s happening in the world?”

DI: Joe and I talked about that at great length when COVID hit us, but there were so many other things going on here that COVID was a lagniappe to this.

FR: I wouldn’t expect you to turn it into a show about COVID, but still, thematically, in terms of the existential issues for the characters, the equivalent was happening to all of us involuntarily.

JM: Correct. But the predicament of the characters was a complete and total abstraction when we did that workshop in 2017.

AS THE PANDEMIC spread in May 2020, Mantello migrated to the West Coast to wait out the shutdown. He and Ives stayed in touch while Ives and Sondheim again started fiddling intermittently with All Together Now.

An email exchange in May 2020:

From: David Ives

To: Joe Mantello

Dear Joe,

You made me a wonderful gift of a Sondheim bag from the National Theatre and I have to say this bag is designed for pandemic wear: it holds just the perfect amount of groceries, gotten by standing in line (impressing people with the bag) and then scampering through aisles furtively grabbing cans of tuna and trying to get the hell out before you catch anything. So thank you all over again.

I hope this finds you well. I’ve been “working” with Steve on All Together Now — lots of ideas, lots of phone calls, lots of rewriting (by me). I find myself in a very odd Pirandello play where I’m collaborating with someone who wants to seem to be writing a musical but doesn’t want to actually write a musical. Years ago I wrote a play for teens that turned out to be quite popular in competitions: it’s a child who shows up for a piano lesson with an eccentric old piano teacher, only there’s no piano. But the teacher makes the child play as if there’s a piano. Little did I know I was prophesying my own future …

Drop a word and let me know how you’re doing if you feel like or have a minute. Crazy times.

From: Joe Mantello

To: David Ives

Dear David,

I’m sorry to hear the update … It’s difficult to imagine things changing radically — I just don’t think his heart is in it. Unfortunately. I was somewhat joking when I wrote to you several weeks ago about Buñuel being the perfect pandemic musical, but now — and I’m saying this only to you — I’m slightly more serious. I don’t think there’s anything to be done about it. Perhaps when things open up in the next few years we can do some sort of benefit staged reading. I really do think it has a new kind of relevance now. It addresses what’s going on in the world in an indirect metaphorical way. Yes, you may have stumbled onto it, but isn’t that always the way?

Joe

From: David Ives

To: Joe Mantello

Joe,

You may be right about Buñuel … There was a day recently when I thought about proposing going back to it. I think frankly part of the reason I didn’t is that it’s just too dark in there. All Together Now at least gives room for more light. And playfulness. And he came up with a structural idea that improved things instantly. Do you think a 90-year-old man really wants to get locked into a room with nothing? I don’t think so. In any case, in Pirandellian fashion, I’m happy to enable him to think he’s working on a musical. What the fuck. On my end, it’s fun.

David

From: Joe Mantello

To: David Ives

Yes, dark, but as we also have newfound understanding of what it means to be trapped in a room with the same people for days on end, perhaps there’s also the comic absurdity of the situation?

I think an audience might relate to that in a completely different way now. It’s no longer surreal, or surreal in the way that it was 2 years ago. It’s the new normal.

But yes, I get why it ain’t gonna happen.

J.

AND BUÑUEL didn’t happen. Ives and Sondheim kept doing sporadic work on All Together Now through the first pandemic year of 2020, with Sondheim sending along bits of lyrics for that rebooted project into the fall, after which work on it petered out too.

JM: I had been incredibly sad when Buñuel was set aside because I really believed in it. I believed in it from the first moment, from the first reading that I saw, even in those early developmental stages. I had been disappointed when Steve and David moved on to All Together Now. I thought Buñuel was special. I felt for Steve that he was having trouble cracking it, but I also thought that he wasn’t taking into account what was actually there.

IN MAY 2021 — a full year after Ives and Sondheim had dropped Buñuel and resumed fitful tinkering with All Together Now — Mantello had a eureka moment of sorts triggered by the seemingly unending isolation of the pandemic. He saw a path by which the three of them might yet regroup and finish Buñuel after all.

JM: I remember sitting in my house, like all of us, and thinking, This is absolutely surreal. There was no end in sight. There was a real lack of contact with friends and loved ones unless you saw them on a computer screen. What we were experiencing was unimaginable, and it occurred to me that this was in fact what the second half of the show might be about. There was something inherent in the piece that we weren’t aware of at the start, this idea of people being trapped inside a space because of some sort of existential terror outside. We needed to attack the section after they realize they can’t get out of the room — to take it seriously. You have to resist going back to the first act’s tone of social byplay. I floated my idea to David initially, but said, “I’m not sure about this. Don’t say anything.”

DI: Joe put the hook in and let it sit awhile. But when we talked, I remember he kept saying, “The show is finished, it really is finished, and this is why and this is why and this is why.” And it was that moment when you’re working on a show and the director points out some key thing and you realize, Oh, wait a minute, I didn’t see that about that character, or, Oh, I understand that scene now. And suddenly the whole show opened up in a way and I thought, Yes, you are right. It had been out of my hands and suddenly it felt like it was back in my hands. I had thought it was in Steve’s hands, but actually it wasn’t. It was so powerful to have the freedom of going back to work on it and just letting loose and taking it seriously, as Joe said, in a way that I don’t think we had before.

JM: I felt that perhaps one of the things that Steve was struggling with was that once these characters realize that they could not leave this room, the score had to change. Because he had written up until the moment when they discover that for whatever reason they are unable to leave the room, and what he was struggling with was everything that came after.

DI: Steve was constantly saying, “Why are these people singing when they’re in this room?” … I would also mention that long before we got to 2021, he sent Joe and me some reading on Buñuel and pointed out that Buñuel had chosen not to have a score in The Exterminating Angel.

JM: Buñuel must have felt that there was nothing that music could add to this story, because he chose not to have a score. I thought, Oh, we’re on the right track. The story is about the absence of music. Once they are trapped in a room, these characters expressing themselves in a conventional musical-theater way would be deeply unsatisfying and detract from the story. One of Steve’s big rules was content dictates form. We had to understand that the absence of music was the score. We had to find a way to satisfy the theatrical demands of the piece while coming at it from a different point of view. So that’s basically what I pitched to Steve. I said, “I believe that this piece is finished, and I could make an intellectual case why the piece is finished. What I’m asking for is permission to go back in and present an idea, a way of tackling this that doesn’t involve you writing any more music.” I recall him being very open to it. He was really curious about what this latest inspiration was. I didn’t really have a clear vision. It was like we were walking on the moon at that point. We didn’t know what it was going to be, but we thought perhaps this was the answer that we’d been searching for.

DI: And in fact, just to show how open Steve was to this, I said to him before we went back to work, “We may have to disrupt some of your work in Act One as we go back over this,” and that it wasn’t going to be set in stone. He said, “Go ahead and disrupt.”

JM: Steve said, “I would want to keep working on it.” I said, “Well, absolutely. You’re Stephen Sondheim. But if you and David give me permission to develop this, I don’t know what the vocabulary is once the conventional score stops, but I bet we can find something that’s as interesting and as experimental as the first half.” That’s really when we all made the decision to start to reinvestigate what it might be. Somewhere around that time, right before James’s book on Sunday in the Park came out, he sent it, and I read it and I found it hugely reassuring. I was reading these stories of James’s experience of writing that show with Steve, and they were almost an exact mirror of what we were going through. And though the birthing pains were difficult, I took great comfort in the fact that others had been there before us and that the end result was wonderful.

DI: We should also remember that if you take Steve’s perspective for a moment, you will understand why he was open to Joe’s idea. Because this actually was light in a tunnel where there had been none before. He didn’t know what we were going to come up with, but some part of him must have wanted to go back to it and see what we had. I think it gave him hope.

WITH SONDHEIM NOW onboard with the plan, late June through July 2021 was a period of intense work for Ives and Mantello. Ives dug into writing “interludes” for the second part that he saw as “a kind of prose equivalent of a song.”

DI: By the time Joe and I spent those six weeks working on the script, we had been in the midst of COVID for over a year. We knew some of the symptoms of being in a room.

FR: How was music to be treated in the second part?

DI: We always presumed, and we discussed this with Steve, that there would be some kind of music there, but as Joe has often said, a dance arranger could almost do it, because it is not song, and Steve understood that. These were all ideas that we were discussing in that summer of 2021.

JM: Initially, I said, “Well, let me figure out what these interludes are.” My original thought was that they would be sort of Pina Bausch movement-driven interludes that leaned into the Surrealism and the more dreamy aspects of the story. But we also discussed the fact that they could be handled in a number of different ways. David, your technique is so precise and you are aware of the fact that in Act Two, you have all 11 characters onstage the entire time. I remember saying to you, “Let them speak. Let them speak.” Let’s see what they have to say. Don’t worry about stage time. Editing is easy. Opening night is a long way away. Just let them speak. That’s how we are going to peel away at who these people actually are.

DI: It was the best advice anybody could have given me. I think that those interludes are the way they are because Joe said that.

JM: The new tone and seriousness of Act Two taught us a lot and became the foundation for our ongoing work on the interludes. The tone is not completely different, but as David continued to write, there’s this gradual deepening of the characters, and I thought, Oh, the Pina Bausch idea is no longer relevant. We can use these interludes as part of the rhythm of the play, but they can be scenes that have an underscore to them. We’re not inventing new themes. They would be based upon and built on the music that existed already. It would be a collaboration between Tunick and Alex. So that’s what we presented to Steve.

DI: Steve liked what he saw, and Joe said, “Let’s set up a reading so you can actually hear it,” as a way of furthering Joe’s case. That was when Joe set up an extraordinary reading with Nathan [Lane] and Bernadette [Peters] and a room full of extraordinary people.

IN LATE AUGUST, a couple of weeks before the reading, Mantello checked in with Sondheim and Ives.

From: Joe Mantello

To: Stephen Sondheim, David Ives

Hello gents,

I returned from my Croatian Vacation last evening and wanted to check in on Buñuel. Steve — I’m eager to see what you’ve been working on — even if it’s still in process. Is there anything you feel comfortable sending along?

From: Stephen Sondheim

To: Joe Mantello, David Ives

Welcome home.

Sorry to report that I haven’t accomplished much in the past two weeks, due to what is euphemistically called health issues. Which aren’t dire, thankfully, as I found out yesterday when I went into NYC to see the appropriate doctor. Being an alarmist (vs. a hypochondriac), I let it distract me all week.

I’m also having eyesight problems, but I’ve got an order in for some enlarged music paper so I can see where the dots are supposed to go. Between the lines? On the lines? You wouldn’t know from looking at my notation — or perhaps Seurat has finally entered my body and has turned me into the first Pointillist composer.

All of which is to say that I’ll get you something this weekend, and let’s talk next week.

You have solved one rhyming problem for me, though, Joe, with your Croatian vacation. I’d been trying to rhyme Dubrovnik.

Czeers (as we say in Czechoslovakian)

From: Joe Mantello

To: Stephen Sondheim, David Ives

Thanks Steve. I look forward to reading what you’ve been working on. Any notes, ideas, thoughts would be of interest at this point … and then we can schedule a time to talk next week.

I understand getting stuck on a rhyme for Dubrovnik. It’s an almost impossible task when one is so lovesick.

Joe

(thankfully — not our lyricist)

From: Stephen Sondheim

To: Joe Mantello, David Ives

Sorry, no cigar. You gotta rhyme the accented syllable first (in this case, the “brov”). But, as Will S said (approximately), the trying is all

Steve

THE COLD READING with Lane and Peters was held September 8, 2021. Sondheim just wanted to hear the lyrics and book; the cast didn’t have to be taught the score.

DI: The fundamental shape of the show was already there at that September reading. The three Act Two interludes were the open and interesting question. But we knew where they were going to be placed, and I’d drafted some ideas for what could be said within them. The actors gamely tried out that material for us at the reading.

JM: Steve was so enthusiastic afterward. He felt like we had a viable show. He felt that he still wanted to continue to write, but there was agreement we were going to move forward with the show as it existed in its current form.

DI: This may be my imagination, but I believe we were sitting at the table after the reading in the empty room and Steve said, “Yes, I think you should go ahead,” because he liked what he had seen. I should also add that day was the last time that I ever saw Steve physically. I walked him out to his car and saw him off literally into the sunset.

FR: Did Steve’s advanced age make you anxious about completing the work before he died?

DI: Steve was too vital for it to affect me that way. I never thought of him as an old man. He felt like my contemporary. Which is what everybody feels like when you’re in the room collaborating. Everybody is as old as you are, which is 12.

FR: His age was never referenced?

DI: I do remember that I took exception to some dialogue he added, and he said, “Hey, I’m an old man.” There was another time, when I took exception to a lyric or a line of dialogue, and he said, “Come on, I’m an icon of the American musical theater.” When he had turned 80 and there were all of those celebrations around town, just endless celebrations, I brought him a bottle of wine, and he said, “This is good stuff.” I said, “Well, you don’t turn 80 every day.” And he said, “Apparently you can!”

FR: He had his aches and pains and balance issues but never seemed frail.

DI: He was certainly spry at the last reading. He showed up on a cane looking quite trim. He’d been up in Connecticut for the longest time, keeping away from COVID. I hadn’t seen him physically in a while. He looked great. He was very with it. He was chatting away with the actors. Of course, he was among old friends like Bernadette and Nathan. I never had that sense anywhere in the process that he was an “old man.”

JM: I completely agree. He was endlessly curious. He was sharp. He was, if anything, too rigorous, too hard on himself. I wonder if at a certain point, with the pressure of being Stephen Sondheim, paralysis sets in. I can’t remember what part of the show we were working on, but he said, “I don’t want to repeat myself. This sounds like, ‘Blah, blah, blah’” in one of his shows. And I thought, Wow, I’m not getting that at all, and I consider myself pretty well versed in your work.

DI: He was a self-tormentor, really.

ON SEPTEMBER 15, 2021, less than a week after the reading, Sondheim went on the Stephen Colbert show to talk about the Broadway revival of Company, which was preparing to resume the previews halted by the COVID lockdown in March 2020.

JM: And he was his self-effacing but gregarious self and he announced to the world that Square One is the title. Our jaws dropped. It was not an agreed-upon title. It was one of many titles.

DI: I wish he could have seen me shooting from my chair and saying “What” … Square One was one of a million possible titles, and there was a time when the list of titles went on for four pages. Steve used a dentist’s appointment as a way of getting out of writing for that week, and so Joe suggested we call the show Gingivitis.

JM: Here We Are was always in play, and at the end of the day, we just felt like it encapsulated the show. It was an arrival at a destination, it was a state of being, and, ultimately for me, I think it’s sort of an offering, Here We Are. It’s also a waiter setting a plate down in front of someone who’s dining there, and that’s how we arrived at it.

FR: It also sweetly bookends Away We Go!, the original title of Oklahoma!, the first show Richard Rodgers wrote with Steve’s mentor and surrogate father, Oscar Hammerstein, and which in 1943 set the young Steve on his path to Broadway.

SONDHEIM TOLD PAPPAS that he was officially authorizing a production of Here We Are. The producer Tom Kirdahy was enlisted to make it happen. The plan was to put it up while Steve was still around to see it. To tamp down over-the-top expectations, it was agreed that the piece should not be staged at a commercial venue or at a nonprofit theater like the Public with a track record of sending productions on to Broadway. “If we could do it in the atrium of the Guggenheim or Whitney, we would,” Pappas was fond of saying.

JM: We all felt that having it produced in the commercial arena was not the way that we wanted to go. We wanted to find a space that was as unexpected as the show itself. When the name Stephen Sondheim is on the project, and I think he felt this more acutely than anyone, there’s an incredible pressure. And so what we wanted to do was to reclaim ownership of the context for this piece. I think we’ve all gone into this as a valedictory lap for Steve, that it is the punctuation on an extraordinary career but we are going to do it on our own terms.

FR: And on Steve’s terms, I’d say. He always talked about his conviction that musical-theater songwriters never wrote anything good after they turned 60. And he was mindful that the giants often went out with Broadway fiascos that were embarrassing derivatives of their classics, like Irving Berlin’s Mr. President and Rodgers’s I Remember Mama. Here We Are differs in shape from any of Steve’s previous shows. For me, it feels like a little bit of a requiem, a little bit of a last testament. When I think about it, I don’t think of musical-theater analogues, including in Steve’s own career, but of spare, late-career experiments, whether by playwrights like Pinter and Albee or artists like Matisse and Klee. A distilled, smaller-scale version of a life’s work that is still powerful and dense with the art and humanity of its creator.

DI: I think the fact that he decided to work on a musical based on two Buñuel movies tells us he didn’t want to write I Remember Mama or Mr. President. But speaking to your point about his age, I think that one of the reasons why he was slowing down in 2018 was that he was getting closer and closer to a story about people who enter a room that they can’t get out of. That must have been working on him subconsciously. And the drag of that was what became palpable to me. I heard from him all the time that nobody ever wrote anything after a certain age, and I said to him, “Verdi wrote Falstaff and Otello after he was 70,” and Steve said, “I hate Verdi.”

AFTER THE FINAL reading, work on the show continued.

DI: I was still talking to Steve pretty much every other day. Of course, he had a million things to say about what he had heard in the room. We were going to continue working on it. A lot of the talk with Steve was about the shape of the show. It’s not surprising since part of what makes Sondheim shows great is the shape of them, the form, the way dialogue falls naturally into song and the way songs give way to book. Some of our conversations had to do with how the songs he’d written fit in. Was the lead-in right? Where does the button fall, should the song even get a button, or should we hold off applause for a better moment? Everything has to feel inevitable. That’s where Steve’s eye went, to the big and small things that made for inevitability.

FR: What was the process after Steve died?

DI: Joe and I cut and moved and reshaped the interlude book material into what is in the show we’re putting up. But we never touched Steve’s work. At that final reading in September ’21 we had proposed a two-line cut in one of his lyrics and he was fine with that. He could see it strengthened what he’d already written. Otherwise, in the show you have the music and lyrics as he wrote them. All the work Joe and I have done since Steve died has been within the book.

FR: In a sense you were custodians as well as the co-creators of Steve’s final show. Did you feel you had the weight of this musical-theater giant on your shoulders?

DI: It never weighed on me. If I had to describe this process of eight years on this show, it was fun. Even when he wasn’t writing. It was always fun with Steve. He loved to have fun. I never thought about this being his last show. I’ve been doing this for a long time. My first professional show was 51 years ago. So this was part of a continuum. I had six shows in ten years at Classic Stage. I had all of this other theater life going on, and Steve was in the mix of that. And it was never a duty. It was never homework. It was fun up through that last reading. He loved things that were new and he loved to be surprised. So part of the job was to keep him interested, keep him amused, and surprise him.

FR: He also loved to laugh. He had a great sense of humor. It’s not for nothing that he wrote A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum early in his career.

DI: Nobody laughed faster or louder or cried faster than Sondheim.

JM: Yes.

FR: The crying was amazing.

DI: He’d be talking about some old movie with Margaret Sullavan and he would say, “Oh, I’m going to cry,” and he would start to cry. That thinness, that thin layer between him and his emotions, is partly why he was as great as he was.

ON THANKSGIVING, Steve did what he did in the years before the pandemic. He and Jeff gathered with a circle of close friends who were Connecticut neighbors. This Thanksgiving the dinner was at Marsha Mason’s house. By all accounts, Steve was the life of the party, as fizzy as usual. He started to feel ill once he and Jeff made the short drive home, sometime after which he collapsed. Jeff called 911 to summon an ambulance, but Steve never regained consciousness and was pronounced dead at the New Milford Hospital at 1:50 a.m. Friday morning. The cause of death was atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Jeff stipulated that Steve’s “usual occupation” on the death certificate be listed as “Song Writer.”

JM: I do think that something shifted when he died. A third of our team is not with us, but he left us such rich material, and what’s the right thing to do? And I think we worried that perhaps one day this show was going to be unearthed and someone was going to look through all of the drafts and notes and assemble a Frankenstein of this show. And we thought, Well, only the three of us knew what we were making. So, in some way, we had a responsibility to put that out into the world.

FR: And there was never any doubt that you would do so?

JM: There was never any doubt because we had his blessing because that last reading had gone so well. Probably in his mind he may have felt that there was work to do on it, as there always is. And so, in his mind, he would describe it as being unfinished. But I also think that what we knew from that point in the last reading was we were going forward with this draft with the understanding that it was going to be refined and edited, and there were going to be changes, certainly, but this was the draft we were taking out into the world.

DI: Can I just interject here? The irony of the fact that he was working on a musical about people going to dinner and that he died on Thanksgiving. I mean he would be on the phone first thing to laugh about that.

THE SHED WAS BOOKED. The cast was set: Francois Battiste, Tracie Bennett, Bobby Cannavale, Micaela Diamond, Amber Gray, Jin Ha, Rachel Bay Jones, Denis O’Hare, Steven Pasquale, David Hyde Pierce, and Jeremy Shamos.

FR: When Steve died, were you as shocked as I think most people who knew him were, by the suddenness? How did you take it in? How did you try to deal with it?

DI: George Bernard Shaw, upon the passing of a great friend, wrote, “You can lose a man like that by your own death, but not by his.” And Steve is so much a part of my life that, yes, of course it was a shock when he died, but he is always looking over my shoulder as I write. He is laughing at my jokes, I hope, very loudly, and crying a little bit here and there. So I didn’t feel, or I haven’t yet felt, that I’ve lost him. It may be that when we’re through this part of it, I will feel that. But he is much too present to me for me to feel the loss. And I may just be in denial in some way, but I do agree with Joe that when he died, there was a weight suddenly upon us of responsibility. And given that we feel responsible toward Steve, we’ve done as absolutely well as we could, I hope, to carry this forward.

JM: I didn’t have the same kind of friendship with him that David did. I wasn’t devastated. I felt, of course, sad, but I also considered myself so fortunate to have walked along the road with him for a bit. Those moments were indelible, and I got to do it twice with him.

FR: The enormous public outpouring after Steve’s death was remarkable, the more so given that he was considered out of the Broadway mainstream for much of his career. Shows of his that are now considered classics — Follies and Sunday, most conspicuously — received often hostile reviews, did not win the Best Musical Tony, and failed financially in their original productions.

JM: My feeling about him when we’d sit and talk was that there was a part of him, despite all of the birthday celebrations and concerts honoring him, that did feel underappreciated.

DI: I think that America took a long time catching up with Steve. He made it difficult for himself to be accepted because of his infinite variety, because he did not keep producing the same musical.

JM: Fortunately, he lived long enough to watch the reevaluation of so many of his shows. And what you’re saying is true, David. We had to catch up to him. His shows are so deep they really demand that you grapple with them in some way. And it’s why in some sense that what the world makes of Here We Are at this particular moment in time is irrelevant, to me at least. I want him to be celebrated, and I would like for his work to be appreciated. But in some way I think we won’t know for 20 years where this falls in the canon of his work.